Burns Night celebrations are held every year on 25 January to mark the Scottish poet Robert Burns’ birthday. The evening usually includes music, food and performances of our national poet’s work. Delving into our archives, we have put together our own step-by-step guide to the perfect Burns Night Supper.

The first Burns Night

The first Burns Night supper was held on 21 July 1801 at the cottage where Burns was born in Alloway. Nine ‘honest men of Ayr’ gathered to mark the fifth anniversary of his death, led by Reverand Hamilton Paul. The supper included a meal of haggis (and sheep’s head) and recitations of Burn’s verse. Regular meetings of this group and further members led to the foundation of one of the first Burns Clubs in Scotland. Hundreds of Burns Clubs can now be found all over the world that celebrate the life and work of ‘Scotland’s Favourite Son.’ Instead of marking the date of Burns’ death, the date of his birth (25 January) became the day to celebrate the Scottish poet. The first Burns Night included the essential ingredients we still observe today: addressing the haggis, a toast to the Immortal Memory of Burns, delicious food and drink and reciting Burns’ prose. A formal Burns Night today can consist of a number of traditions, starting with the Selkirk Grace.

In more recent times, we start our evening by welcoming guests. A bagpipe player usually plays a traditional tune while the top table is seated. For an informal event, playing music or simply tapping on the table or a glass can be a substitute to get your guests’ attention and give a warm welcome.

Recitation of the Selkirk Grace

Recited by the host in Scots, it gives thanks for the meal which follows. The Selkirk Grace is often said at gatherings on St Andrew’s Day on 30 November, weddings and other special occasions. Although the piece predates Burns’ time, it is now associated with him. The grace says:

Some hae meat and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it,

But we hae meat and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankit.

In English, this can be translated to:

Some have meat but cannot eat,

Some have none that want it,

But we have meat and we can eat,

So let the Lord be thanked.

Address the haggis

The centre piece of the meal is the national dish, haggis, or as Burns called it ‘Chieftain o’ the puddin-race!’ Haggis has been eaten for centuries in Scotland. After a successful hunt, the offal of an animal needed to be eaten quickly, so they were packed into the stomach of the creature and cooked. At a contemporary Burns Night celebrations, the haggis is served with ‘champit tatties’ or mashed potatoes and ‘bashit neeps’ or mashed turnips. In England turnips are commonly called swede and in America the vegetable is known as rutabaga.

A description of haggis or ‘Haggase’ can be found in a record from our archives. Consisting of the

“belly of a sheep, filled with minced meat, Blood, Onions & herbs. A dish much eaten by the common people of Scotland. It is always sent up very hot, and when cut, smokes and the Air coming out makes a noise.”

NRS, Papers of the Drummond Family, Earls of Perth, GD160/566/11

Haggis has been eaten by all Scottish society. The Duke of Montrose describes how most of his household, upstairs and downstairs, were taken ill after eating ‘hagiss’:

“My wife, the two boys and 8 of the servants were all taken at a violent cholick & griped an a great purgeing on Wednesday […] a Scots dish ordered a Hagiss […] and I take it for granted that some of the herbs that were put into it have been poisonous since all that eat of it have been ill of the same disease […] and according as they eat less or more they had the disease to a greater degree however god be thanked all are now well.”

NRS, Papers of the Graham Family, Dukes of Montrose, GD220/5/835/16

Dinner is served!

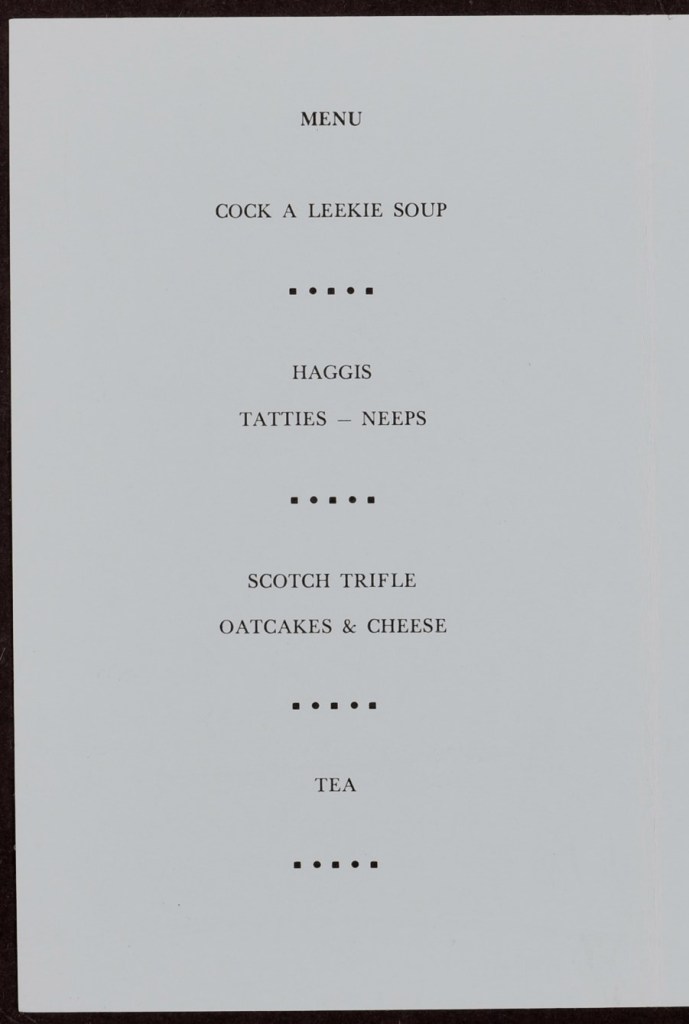

The three courses start with a wholesome soup. Cock-a-leekie is a popular choice, being a traditional Scottish soup with the primary ingredients of chicken and leeks. The original recipe had prunes added for sweetness and the soup is thickened with barley or rice. This was the choice of the South Leith Parish Church Women’s Guild in 1980. Their ‘Burns Supper’ was held at South Leith Church Hall on Tuesday 22 January that year and their menu has been preserved in the collections of the Church of Scotland.

Although their supper seems to have swapped the whisky, which usually follows the three courses, for tea.

The dessert offered is often a trifle, called a ‘Tipsy Laird’. Differing from the English equivalent, it is laced with whisky, rather than sherry. Cranachan is another popular dessert combining fresh Scottish raspberries, oats and thickly whisked cream mixed with whisky and honey.

A wee nip

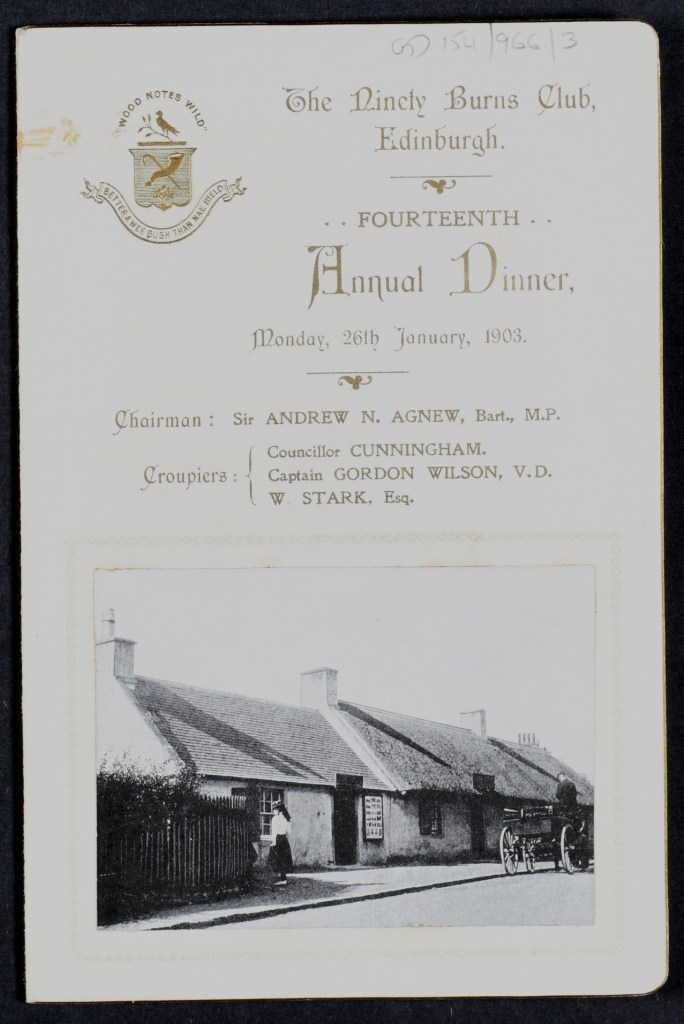

The meal is rounded off with a wee nip or dram of ‘aqua vitae’ or, Scotch whisky. At the Ninety Burns Club, Edinburgh a 15-year malt whisky was offered to guests at their annual dinner on 26 January 1903. The programme card is beautifully illustrated with an image of the cottage where Burns was born, in Alloway in 1759.

The following pages sets out the decadent menu or ‘Bill of Fare’, giving details of the aged whisky and an additional fish course.

The toasts

After enjoying their meal, guests are entertained by various toasts to give thanks to the Scottish bard and those who provided the supper. Traditionally these are often interspersed with music and song. The Ninety Burns Club evening was accompanied by several Burns songs, including ‘A man’s a man for a’ that’ and ‘Bonnie wee thing’. There was a violin soloist for several of the musical interludes and the singers were accompanied by a piano.

The immortal memory

At this point of the evening we remember the life and work of the Scotch bard, Burns himself. The Ninety Burns Club dinner had their Immortal Memory of Burns presented by William Jacks, MP, and published author on Burns.

Edward Tennant, Lord Glenconner, gave his Immortal Memory shortly after the First World War. His son died in the conflict and was a war poet. In Lord Glenconner’s notes for his address to those gathered for the Burns Night Supper he poignantly pondered what Burns, a man who loved “Freedom and [had] a hatred of Tyranny…a few months ago he might have said to Belgium,

See stern Oppression’s iron grip,

Or mad Ambition’s gory hand,

Sending, like blood-hounds from the slip,

Woe, Want, and Murder o’er a land!”

This last passage Glenconner had taken from ‘A Winter Night’ (1786). Glenconner goes on to say that Burns’ “songs are part of the mother tongue not of Scotland only but of Britain and of the millions that in all the ends of the Earth speak our language”. Perhaps Glenconner has identified the reason Burns and his work are still celebrated throughout the world.

A toast to the lassies

This part of the evening offers some light relief after the serious business of the Immortal Memory. It considers the relationships between men and women, using the poetry of Burns, contrasting, and celebrating the differences between the sexes.

On 25 January 1980, BBC Scotland’s long running radio programme ‘Odyssey’ presented by Billy Kay celebrated Burns Night with an episode entitled ‘I Hae Lo’ed’. Kay introduced a selection of poetry and song all on the theme of love, with live musicians taking part in the transmission. The popular Burns poem ‘Ae Fond Kiss’ and the song ‘My Wife’s A Winsome Wee Thing’ were included and may have supplied the perfect soundtrack to a Burns Supper taking place in homes across the land (NRS, BBC1/4/105). The 28-minute long programme appears to have been a success and repeated on Burns Night in 1981.

The toast to the lasses is responded to by a female guest or guests, in the ‘Reply to the toast of the lassies,’ usually in a humorous or mocking manner.

Vote of thanks

The host rounds off the evening by thanking all that contributed to the meal and thanks the guests for their attendance.

The end

A typical Burns Night supper ends with all those gathered singing of ‘Auld Lang Syne.’ Today we associate this poem with Burns and the celebration of Hogmanay. Sung to a traditional folk tune, it is unclear who authored this poem, as Burns said he wrote it down in 1788 after hearing ‘an old man’s singing’. While not his own work, the poem and song has been associated with Burns and sung at new year since the 1800s.

We hope that you enjoy your own Burns Night Supper, in whatever way you chose to celebrate, but be sure to raise a glass of something to Scotland’s favourite son, Rabbie Burns!

Jessica Evershed

Outreach and Learning Archivist

Resources:

- Clark McGinn, The ultimate Burns Supper book: a practical (but irreverent) guide to Scotland’s greatest celebration, 2010.

- The Legacy of Robert Burns, NRS web archived site: [ARCHIVED CONTENT] The Legacy of Robert Burns – The National Records of Scotland

- Celebrating Burns Night, National Trust for Scotland

What an excellent article, thank you!

LikeLike

“Reverand Hamilton Paul” ??? Surely, this should be ‘The Reverend Mr. Hamilton Paul’…

LikeLike