Coming across photographs amongst bundles of manuscripts is not uncommon within the archives of the National Records of Scotland (NRS). However, this one caught my attention – because when I followed the instructions printed on the mount – he smiled at me. Inscribed on the back: “Geo. France 12/4/17”, material within this collection suggests this is Captain George H. Barton of the Australian Light Infantry – as the star of his own silent ‘movie’

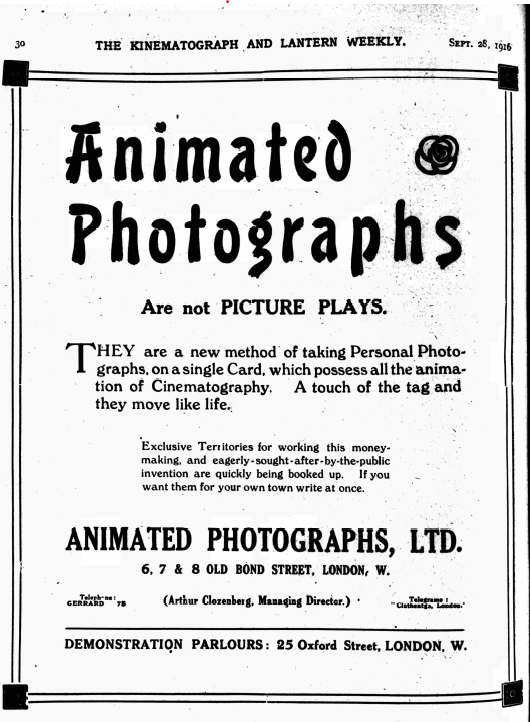

A product of the ‘Animated Photographs Ltd’, the company has left few traces. A couple of full-page advertisements in ‘Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’ dated 21st September 1916 proudly proclaimed: “A new method of taking Personal Photographs, on a single card. Which possesses all the animation of Cinematography.” (‘The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’, London 28th September 1916)

An overnight wonder

On the 3rd of July 1916 the ‘Amateur Photographer and Photographic News’ commented:

“It is quite some time since the last most wonderful invention in the photographic line was recorded. Quite a fortnight at least … then all of a sudden … ‘the most wonderful invention in the way of portraiture that I have ever seen’ … ‘living portraits … not yet on the market’, and ‘the secret of the process is too precious to reveal’ … on Tuesday the Evening News sent a galvanic shock of disappointment right down to my boots. … that the photographs are as old as tea on the other side [of the Atlantic] … on Friday the writer had said that ‘by an almost imperceptible manipulation of the portrait at one side, the eyes suddenly alter their expression’ … But on Tuesday … the writer goes on to be brusque; if not crude. ‘By waggling a tab at the side of the photograph … you may see a man wink, talk and smile’. … What we believed to be a breathing, blushing, palpitating portrait becomes a Jack-in-the-box arrangement, where you get the required movement by the unelusive process known as waggling.”

Amateur Photograph and Photographic News, London 3rd July 1916

It would appear that Animated photographs were already considered a bit passé by the time George had his photograph taken. However, I had never encountered his like within NRS collections, and was intrigued.

The still image moves

Flick-books had long been used to create ‘moving images’ – an illusion based on the persistence of vision and the Phi phenomenon. The first causing the brain to retain images cast upon the retina for a fraction of a second beyond their disappearance, the latter creating apparent movement between images when they succeed one another rapidly. Towards the end of the nineteenth century innovative methods of creating ‘movement’ from still images were developed, of which this item, GD372/293/9, is an example.

In 1890 Britain – Louis Brennan (1852-1932), an Irish mechanical engineer, patented a means of creating ‘Animated pictures’ (BP 2623), which involved a picture printed onto strips of paper: “Carried in a zig-zag manner … pictures … rapidly replace each other, the change taking place simultaneously over the whole extent.” (British Patent 2623, (1890), Louis Brennan). He emigrated to Australia in 1861, and invented a coastal defence torpedo, which he patented in London in 1877. Subsequently the War Office granted him £110,000. Needless to say, he made no attempt to further or commercialise his ‘Animated pictures’.

Evidently ‘moving pictures’ were exciting other people. In 1903 America, Eugene Frederic Ives (1856-1937), patented the ‘Parallax stereogram’, a compound image consisting of fine interlaced slivers of a stereoscopic pair of images seen in 3D when viewed through a separated fine grid of correctly spaced alternating opaque and transparent vertical lines, known as a ‘parallax barrier.’ The grid allowed each eye to see only the slivers of image intended for it. His 1904 US patent 771,824 used the same technique but with differing images, vibration of which, made it appear to change from one image to the other, thus creating an illusion of movement.

In France, only one year later in 1897, Léon Ernest Gaumont (1864-1946), pioneer of the world’s first film studio, encountered Ives pictures at the St Louis World’s Fair and presented them to the French Academy of Science. Taking inspiration from this, mathematician Eugene Pierre Estanave (1867-1937) filed French patent 371.487 in 1906, for a stereophotography device and stereoscopy using lined sheets, that applied the principle of Ives ‘Changing sign’ to animated photography. Once again, none of these methods were developed commercially.

However – In December 1909 US patent No. 944 385A was filed by Alexander S. Spiegel: “My invention relates to picture post cards or the like, and particularly to a moving picture device” ( US patent 944 385 A, (1909), Alexander S. Speigel). Spiegel’s patent found commercial application as ‘Magic Moving Pictures’ manufactured by G. Felsenthal and Co. and also as ‘Magic Moving Picture Card’ produced by the Franklin Postcard Co., both in Chicago. “One of the most pleasing photographic novelties that has come to our notice … is the magic moving photograph … three different poses with varying facial expression are made of a person on one plate … This gives unlimited opportunities to produce pictures that are both serious and humorous … this pleasant and surprising novelty bids fair to become the one great summer-amusement everywhere, for it appeals not only to amateurs, but to professionals who will recognise in it a ready and popular source of pecuniary profit.” (American Journal of Photography (1914)

Meanwhile in Britain – In 1916, Alfred E. Walsham, architectural and technical photographer, of London was busying the patent office with BP 106680: “Plate holder used to produce composite photographs where a mask is moved between successive images” (British Patent 106680 A.E. Walsham, A. Bennett and A.H.F. Perl (1916) and the following year, Reginald Ignatius Atherton (1877-1952), a Norfolk born photographer who had, in 1911, become the theatrical manager of the New Cross Variety and Cinema Theatre, filed his patent BP 114173: “Comprising a composite photograph and a ruled screen enabling the photograph to be exhibited with an animated effect, the photograph is printed on a celluloid base and is mounted in front of a sheet of paper ruled with lines corresponding with those on the screen used to make the negative, the ruled paper and the photograph may be kept in contact by embossing the central portion of the card upon which the ruled paper is mounted. The photograph is carried by a front card which has an oval or other opening and is secured to the back by flexible strips permitting relative movement of the cards” (British Patent 114173 Reginal Ignatius Atherton (1917).

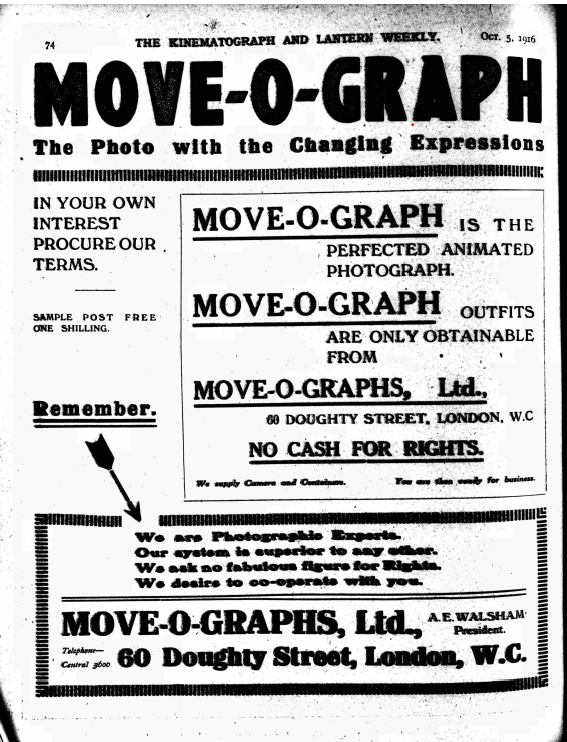

Seeing the commercial opportunity, Walsham established ‘Move-o-graphs Ltd’, some examples of which reference Atherton’s patent. A full-page advertisement for Move-o-graphs in ‘The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’ on the 5th October 1916 declared: “Our system is superior to any other.” Clearly, they were aware that they had competition.

The Animated Photographs Ltd

That competition came from the Animated Photograph Ltd – the company responsible for producing GD372/293/9. Using similar technology, only one month later, they took out their full-page advertisement in the same trade magazine. Their Managing Director, Arthur Clozenberg (1883- 1951) was the London born son of a Jewish family from Warsaw, whose father had opened a furniture making company in East London. By 1909 this was being run by Arthur and his brothers – Joseph, George and Albert.

When a family friend, David Walter Beck, revealed that his father had converted his china shop in Shoreditch into a cinema: “…audiences were moved to cheers, applause and laughter by motion pictures, and how much more profitable they were than selling dinner services.” (Arthur Clavering interview 1931 from kilburnwesthampstead.blogspot). Needless to say, the brothers financed the next conversion -– the Kilburn Empire music hall, which: “… opened on August Bank Holiday 1909 … we lost £50 or so a week for some months … Years later, having made thousands of pounds from it directly, and very much more indirectly, through the incentive it gave us to extend our film activities” (Arthur Clavering interview 1931 from kilburnwesthampstead.blogspot).

It is noteworthy that the first performance of films to a paying audience in the UK, consisting of short films made in France by the Lumiere brothers, had taken place just thirteen years earlier.

As fellow ‘theatrical managers’ the Clozenberg’s were doubtless aware of Atherton and the success of his Move-o-Graphs. Arthur being particularly intrigued, for it was he who was recorded as the ‘managing director’ of Animated photographs Ltd (Company No: 143936) when it was incorporated in 1916. Though the novelty of the hand-held moving image briefly held some magic, it was to be quickly eclipsed by cinema itself.

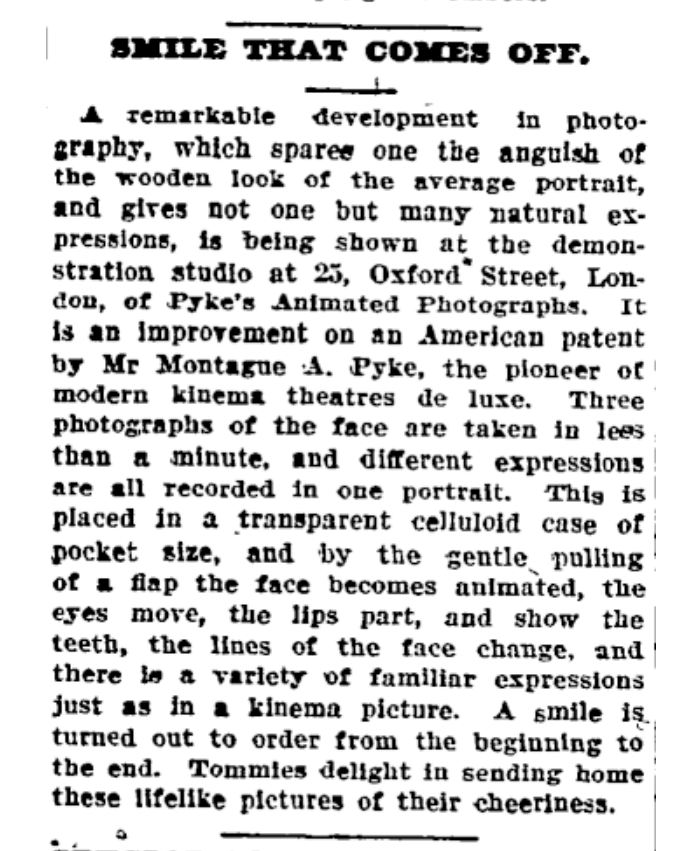

Unsurprisingly, by April 1917, Animated Photographs Ltd had a new Managing Director, Montague Alexander Pyke. Former commercial traveller, gold miner and stock market gambler, he had been declared bankrupt in 1906. Having witnessed Hale’s Tours, on Oxford Street in that year – one of the first full-time film venues in London – his interest in ‘moving pictures blossomed following the 1909 Cinematograph Act, when, with capital of £10,000, but no assets, he opened his first cinema ‘The Recreation Theatre’ on Edgeware Road. Four more followed, forming the Amalgamated Cinematograph Theatres Ltd in 1910. At its peak ‘The Pyke circuit’ operated 14 cinemas in central London.

From a weekly salary of £25 in 1908, he was paying himself £10,000 a year by 1911. However a 1912 committee of Iinvestigation uncovered irregularities which led to him operating only two cinemas by 1913. Divorced, and bankrupt again by 1915, he was also accused (& acquitted) of manslaughter following the death of an employee in a nitrate film fire on his premises.

In June 1916 even the trade magazine: The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly renounced its support for Pyke’s next endeavour with Animated Photographs Ltd: “The kinematograph industry will … regard with some curiosity the announcement of the registration of a company with the above title, whose object is stated to be to acquire and turn to account certain patents or rights relating to an invention … The capital of the company is only £500 … I have been told … that the aforesaid patents or rights are extremely valuable, that the company just registered is going to be the nucleus of the next big thing, and that Mr Pyke … will again loom large in the kinematographic world as he did, say four or five years ago .… I think it … unlikely that Mr Pyke in his new departure will receive any financial support from … the kinematograph industry generally.” (‘The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’ 15th June 1916)

Despite criticism, determined to succeed worldwide, he advertised heavily, taking advantage of every opportunity – even war: “Tommies delight in sending home these lifelike pictures of their cheeriness.” (‘The Auckland Star’, New Zealand 7th October 1916). Indeed George was one such soldier. However, competition from Move-o-Graphs proved too strong: “The ‘Kinematograph Weekly’ cited in court … an action brought by Animated Photographs Ltd., against Mr W. J. Davies … a kinematograph proprietor and furniture dealer at Porth, from which the plaintiffs claimed damages for breach of an agreement to hire three special cameras for producing animated photographs of clients … [and]… mounts [which] gave changing expressions of the face by pressure on the back and slowly bending a flexible flap, whereupon eyes and lips moved, and the whole expression changed … he thought he was getting an exclusive license, but he found the Movographs Co. Ltd. … in … Cardiff … he had looked at their Oxford Street premises and become a victim of their novelty … Mr. Montague Alexander Pike (sic) … explained that the changing expressions were assisted by lines on a celluloid strip. Three photographs of different expressions were taken, and these were manipulated the one over the other, by a movable flap, the photographs were pressed meanwhile … against the celluloid by pressure on the back of the photographic mount. … They were paid £2,000 for the rights for Manchester and Blackpool, £800 for Sunderland, £1,000 for Birmingham, £1,500 for Liverpool, £150 for Bournemouth, and he had just sold the rights for Australia for several thousand pounds. He thought both his process and the results were better than in the case of Movographs … He knew Movographs were present in Court, but he told them he thought they hadn’t anything like the control over facial expression that he had (laughter).” (‘The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’ 5th April 1917)

Less than a year after Pyke had taken over Animated Photographs Ltd it disappeared forever:

‘The Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly’ 9th August 1917

“… Animated Photographs Ltd. – in the Winding Up Court, on July 3rd, Mr Justice Neville, on the petition of C. H. Hewitt, judgement creditor for £320 12s. in respect of work done and good supplied, made an order for the compulsory liquidation of the Animated Photographs, Ltd. There was no opposition.”

Meanwhile Move-o-graph continued to advertised nationally, and franchises opened throughout the country.

“Everybody wants one. – The living photo or mov-o-graph, winks, smiles and laughs, frowns, like life; greatest novelty of the season; selling in thousands; sample 1s, enclose stamp.”

‘The Gloucestershire Echo’ 20th May 1920

“Special notice. Advance orders are now being booked for Move-o-graph Christmas cards (Living picture and card combined). Will amuse both young and old. 1s each, post 1s 2d.”

‘The Orkney Herald’ 30th March 1921

Outliving similar British companies, the novelty finally wore off in May 1950 when the London Gazette finally recorded that Mov-o-graphs Ltd had likewise been dissolved. The era of animated screen photograph had briefly bloomed and then quietly passed, but GD372/293/9 remains, alongside a wealth of photographic material cared for and preserved within the NRS collections by the Conservation Service Branch. Perhaps the reason why so few of its kind survive is that they were often taken apart in attempts to solve the mystery of their movement – novelty both birthed and doomed by cinema.

“The animated screen photograph, with its instructions for gentle handling, its reliance on a very limited number of staged poses, its jerky animation that always looped back on itself instead of moving forwards … belonged to a very specific period in the history of still photography and of animated photography, a moment that also reveals the hopes pinned on both techniques” (‘3D and animated lenticular photography: Between Utopia and entertainment’ by Kim Timby, Studies in Theory and History of Photography Volume 5, 2015)

A footnote: The Clozenbergs and the movies

In 1911 Arthur, and his brother Albert formed a film booking company ‘Atlas Feature Films.’ Two years later, in partnership with C.W and A.C. Lovesey, who controlled Ruffles Imperial Bioscope Ltd, they formed Ruffles Exclusives, which distributed Vitagraph Studios films – the most prolific American silent film production company. Around the same time, like many Jewish families, they changed their name, from Clozenberg to Clavering, without formality. The brothers went on to form the Film Booking Offices Ltd, and in 1921 were successful in purchasing the distribution rights to Chaplin’s ‘The Idle classes’, for which they paid £50,000.

By 1927 Albert Clavering was the managing director of Universal Picture Theatres Ltd, which controlled 16 London cinemas, whilst Joseph continued to run the Kilburn Palace cinema and the Piccadilly Theatre Company.

Arthur (Clozenberg) Clavering stood, unsuccessfully, in 1922, as the National Liberal Parliamentary Candidate for Hampstead, utilising a travelling motor cinema in his campaign. In 1928 he became director of Warner Brothers in England, in the same year renting the Piccadilly Theatre which premiered ‘The Jazz Singer’ (the first feature-length talking picture shown in Europe). By 1930, 150 of London’s 400 cinemas were wired for sound.

This time he’d backed a winner.

Jacqueline Thorburn

Conservator