The “Radical War” or “Radical Rising” of 1820, also known as the Scottish Insurrection of 1820, was a week of strikes and unrest in Scotland that culminated in the trial of a number of ‘radicals’ for treason.

National Records of Scotland (NRS) holds the trial records and to mark the 200th anniversary of this event, a project was launched to clean, image and catalogue these documents (‘The “Radical Rising” of 1820, Part one’ and ‘Part Two’).

The events of the 1820 Rising followed years of economic recession after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and considerable revolutionary instability on the European continent. As the economic situation worsened for many workers, societies sprung up across the country which espoused radical ideas for fundamental change.

In the early 19th century, Scottish politics offered power to very few people. Councillors on the Royal Burghs at this time were not elected to their position, rich landowners controlled county government and there were less than 3,000 parliamentary electors in the whole of Scotland.

It was recognised that the key to change was electoral reform, and the events of the American Revolution of 1776 and French Revolution of 1789 helped to promote these ideas. Radical reformers began to seek the universal franchise (for men), annual parliaments, and the repeal of the Act of Union of 1707.

As the calls for reform increased those in the Government, scared by the events of the French Revolution, were concerned about the possibility of a violent insurrection at home. This fear was perhaps justified. In Scotland a covert group existed called the ‘Committee for Organising a Provisional Government’ which consisted of committed radicals elected by their respective unions, who would assume responsibility of organising a new social structure in Scotland in the event of a successful rising.

It is now generally accepted that to monitor the situation the Government deployed a network of agents or spies, who successfully infiltrated this radical leadership. John King of Anderston, sometimes calling himself John Andrews, appears to have been the Government’s chief agent. The Glasgow police commander, James Mitchell, reported to the Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth in March 1820 that the radicals were preparing a general rising in Scotland. On King’s advice, Mitchell arrested the entire 28-man radical central committee in Gallowgate.

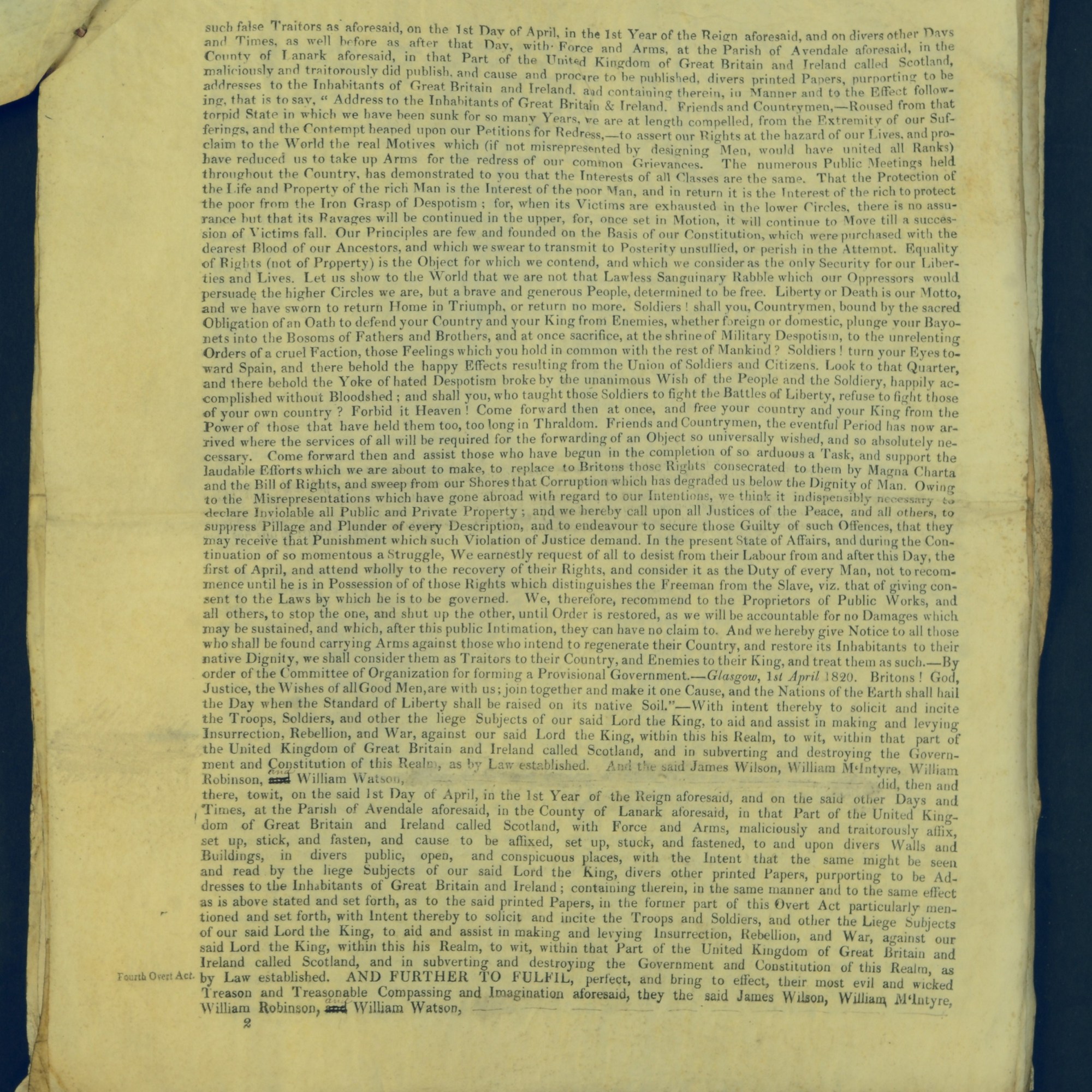

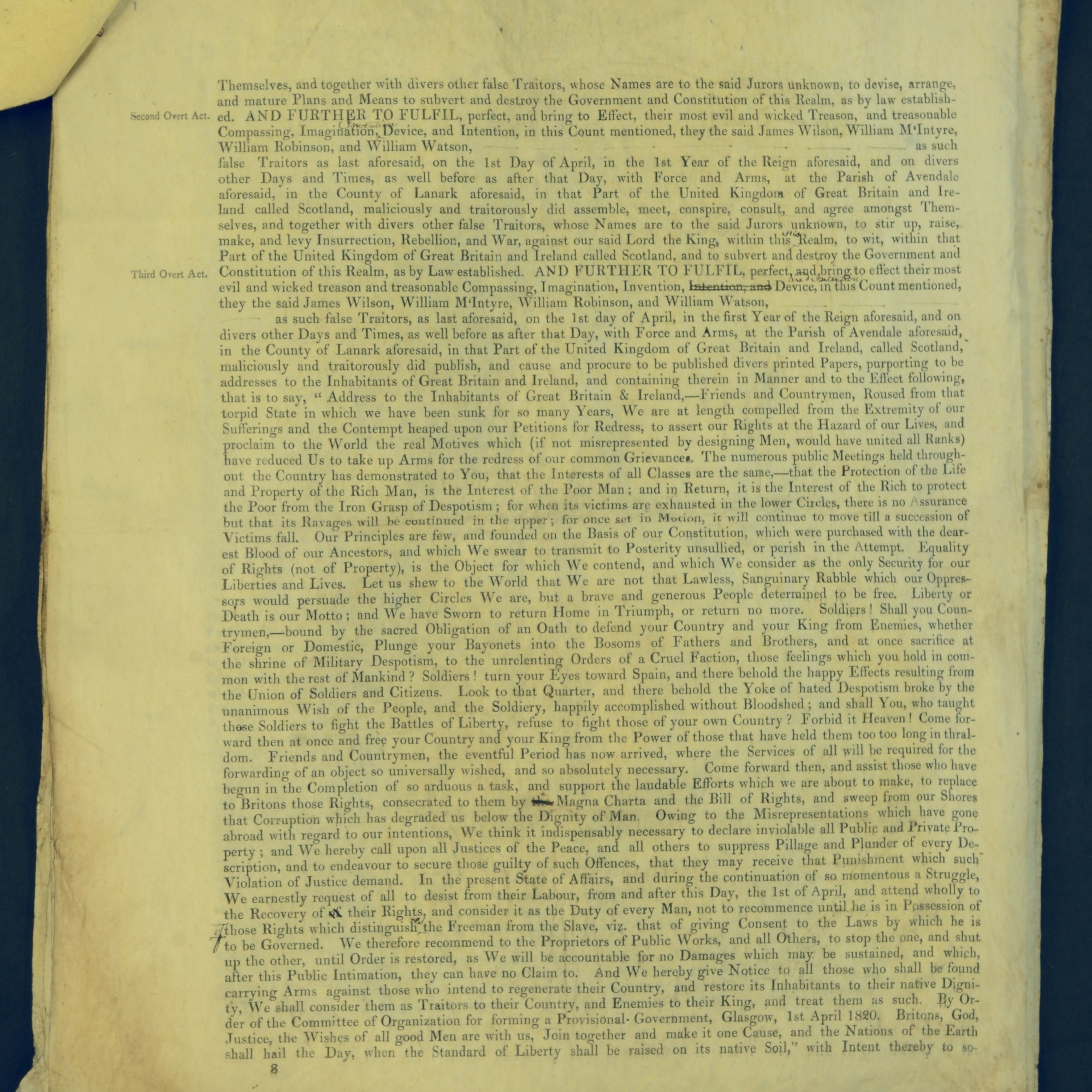

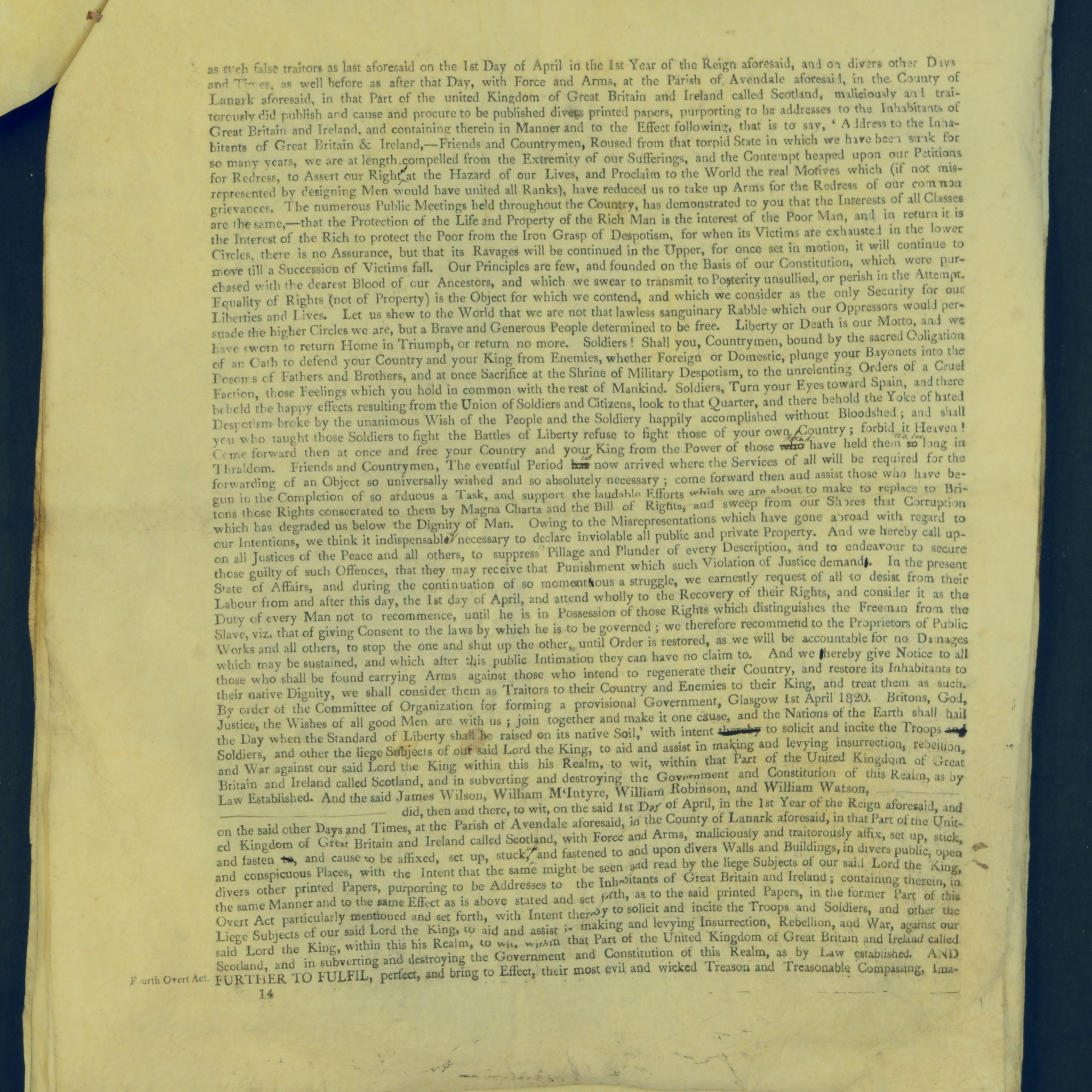

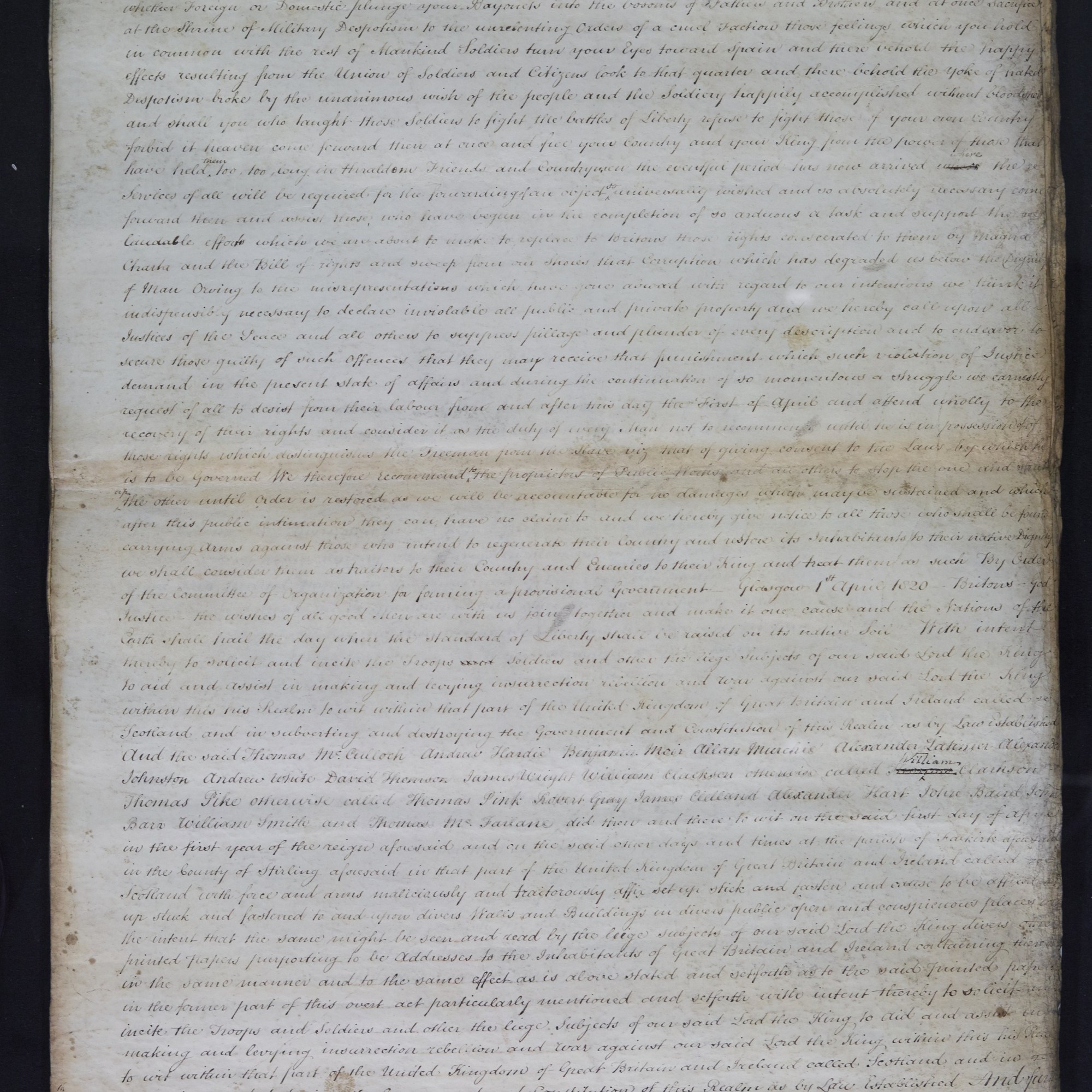

A plot was then hatched to issue a call to the ‘rank and file’ on behalf of the central committee to ‘take up arms’; those that did would mark themselves as radical sympathisers and be removed. On the 1 April 1820 the ‘Proclamation of the provisional government’ appeared around the city of Glasgow:

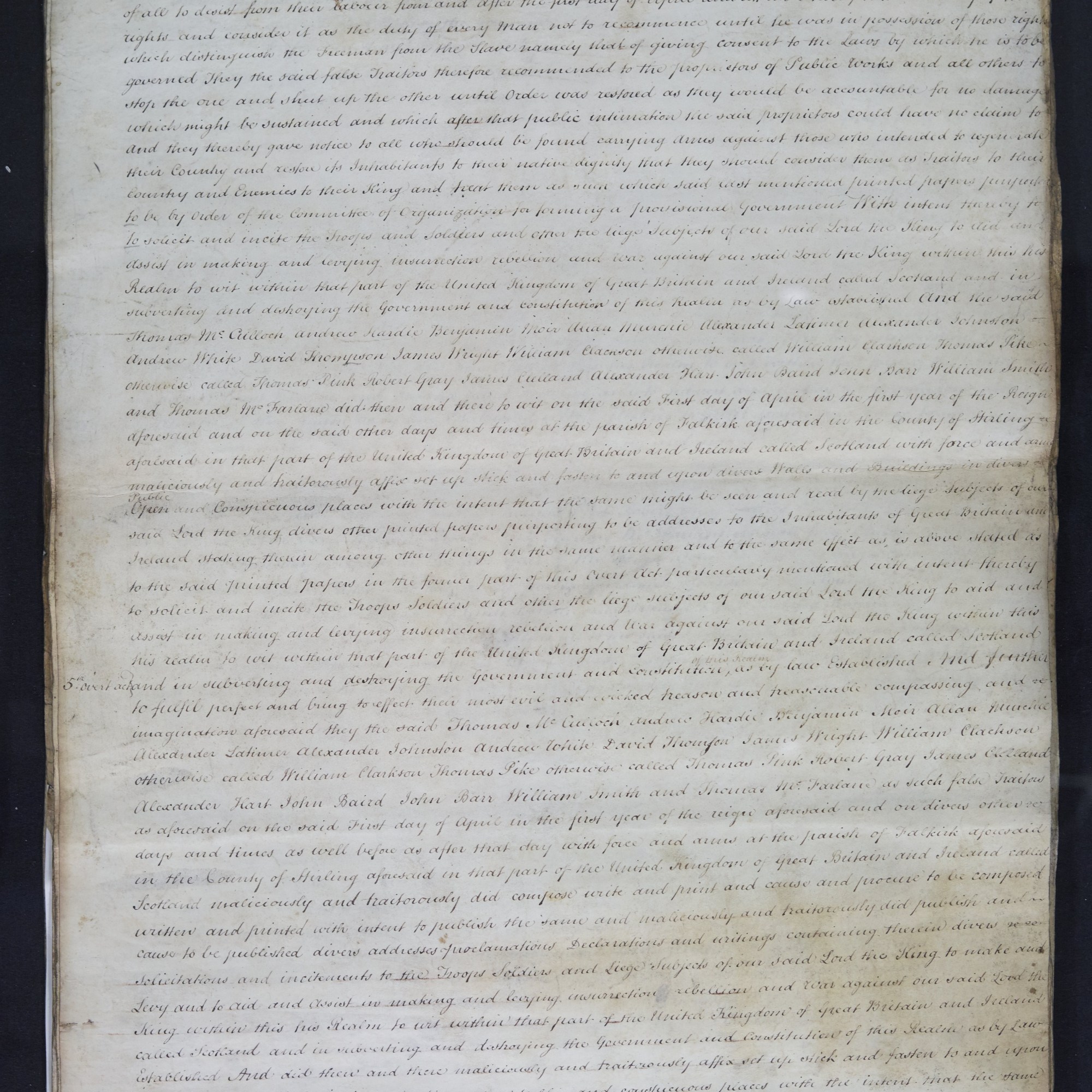

“Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain & Ireland. Friends and Countrymen – Roused from that torpid State in which we have been sunk for so many Years, we are at length compelled, from the Extremity of our Sufferings, and the Contempt heaped upon our Petitions for Redress,-to assert our Rights at the hazard of our Lives, and proclaim to the World the real Motives which (if not misrepresented by designing Men, would have united all Ranks) have reduced us to take up Arms for the redress of our common Grievances… Our Principles are few, and founded on the Basis of our Constitution, which were purchased with the dearest Blood of our Ancestors, and which we swear to transmit to Posterity unsullied, or perish in the Attempt. Equality of Rights (not of Property) is the Object for which we contend, and which we consider as the only Security for our Liberties and Lives… Liberty or Death is our Motto, and we have sworn to return Home in Triumph, or return no more… Friends and Countrymen, the eventful Period has now arrived where the services of all will be required for the forwarding of an Object so universally wished, and so absolutely necessary. Come forward then and assist those who have begun in the completion of so arduous a Task, and support the laudable Efforts which we are about to make, to replace to Britons those Rights, consecrated to them by Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights, and sweep from our Shores that Corruption which has degraded us below the Dignity of Man… In the present State of Affairs, and during the Continuation of so momentous a Struggle, We earnestly request of all to desist from their Labour from and after this Day, the first of April, and attend wholly to the recovery of their Rights, and consider it as the Duty of every Man, not to recommence until he is in Possession of those Rights which distinguishes the Freeman from the Slave, viz. that of giving consent to the Laws by which he is to be Governed… By order of the Committee of Organization for forming a Provisional Government.- Glasgow, 1st April 1820… “

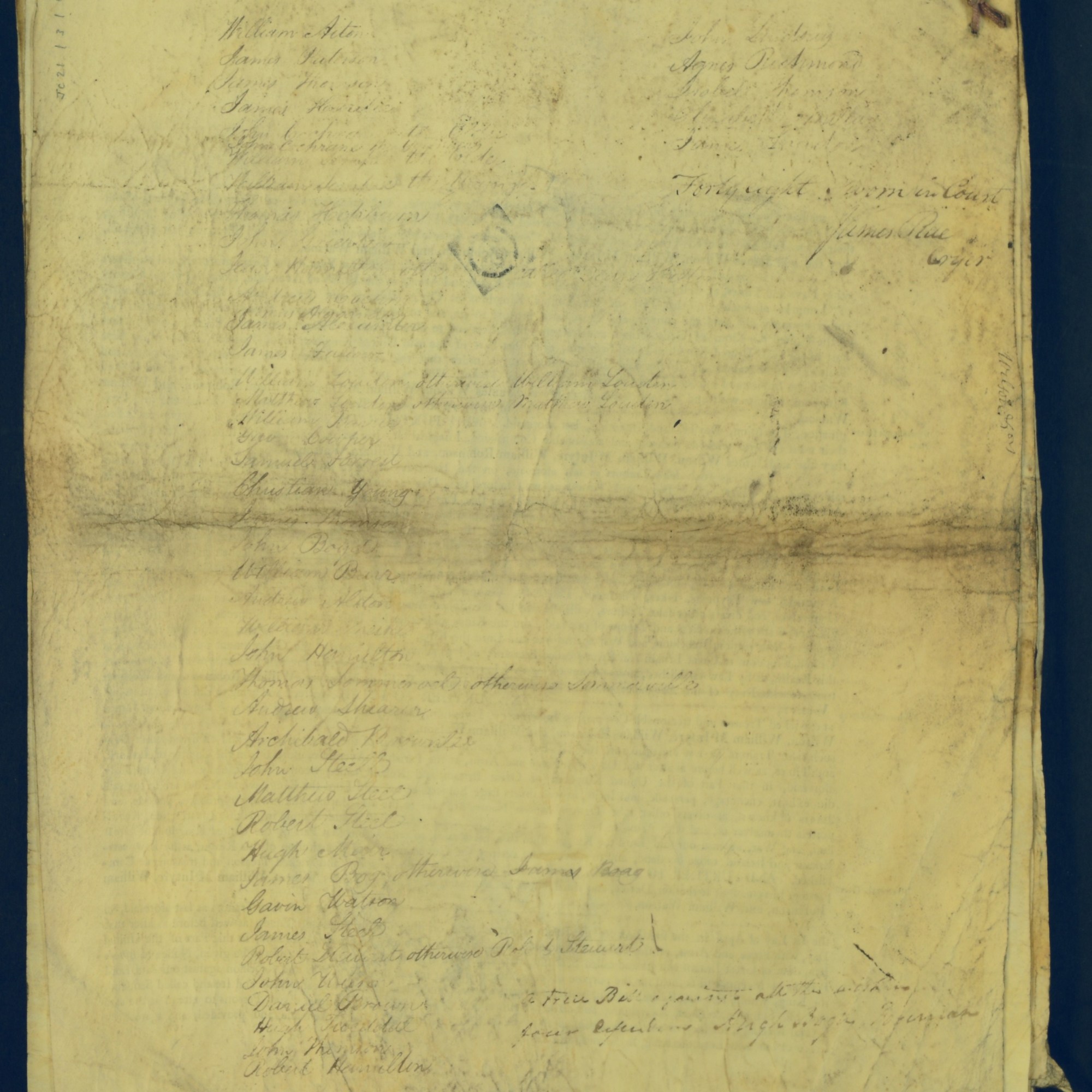

Treason Trials, County of Stirling. National Records of Scotland, JC21/2/2 page 3. Full transcription of the Proclamation is available here.

Across central Scotland in Stirlingshire, Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire, some works – particularly in weaving communities – stopped and radicals attempted to fulfil the call to rise. Several disturbances occurred across the country, perhaps the worst was a skirmish at Bonnymuir where a group of about 50 radicals encountered a patrol of around 32 soldiers led by a Lt. Hodgson. After a volley of shots from the radicals, they were quickly overpowered by a cavalry charge, with two of the soldiers and four of the radicals wounded.

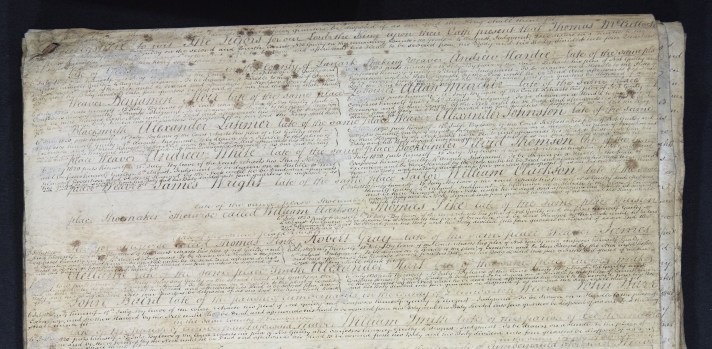

In total 88 bills of treason were issued, but only a few were tried as a significant number had fled the country.

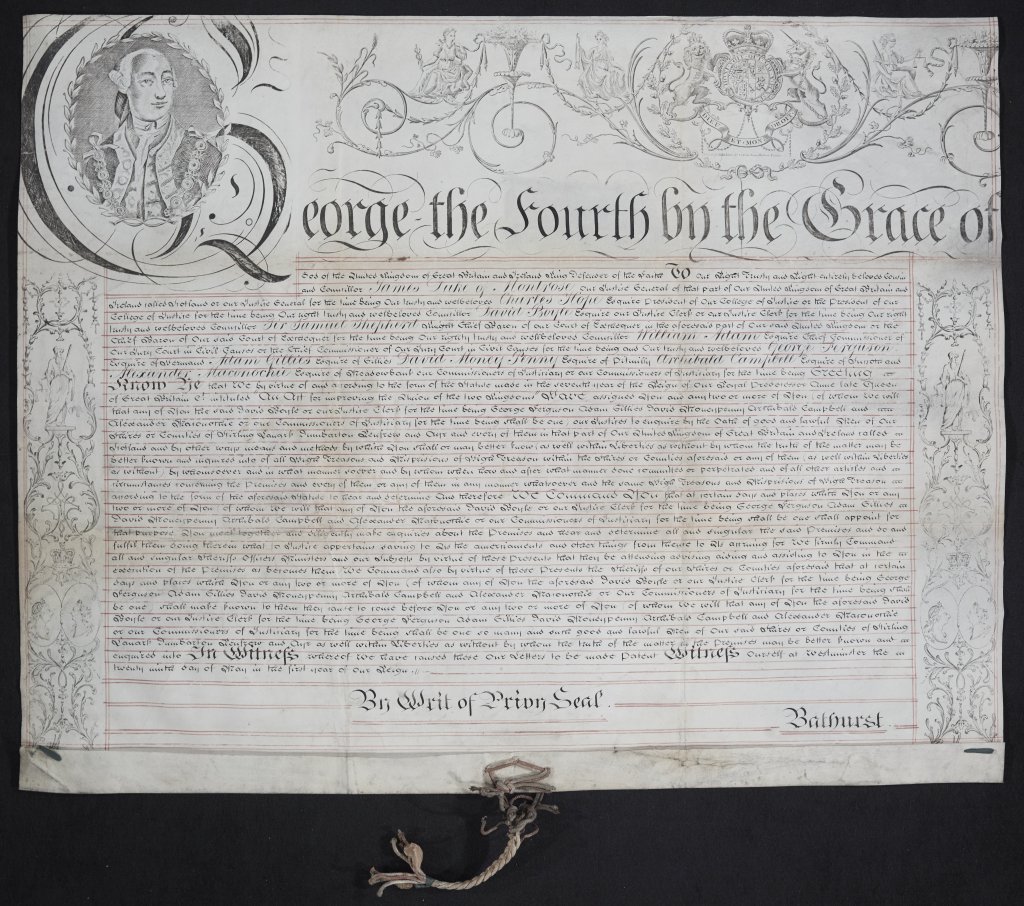

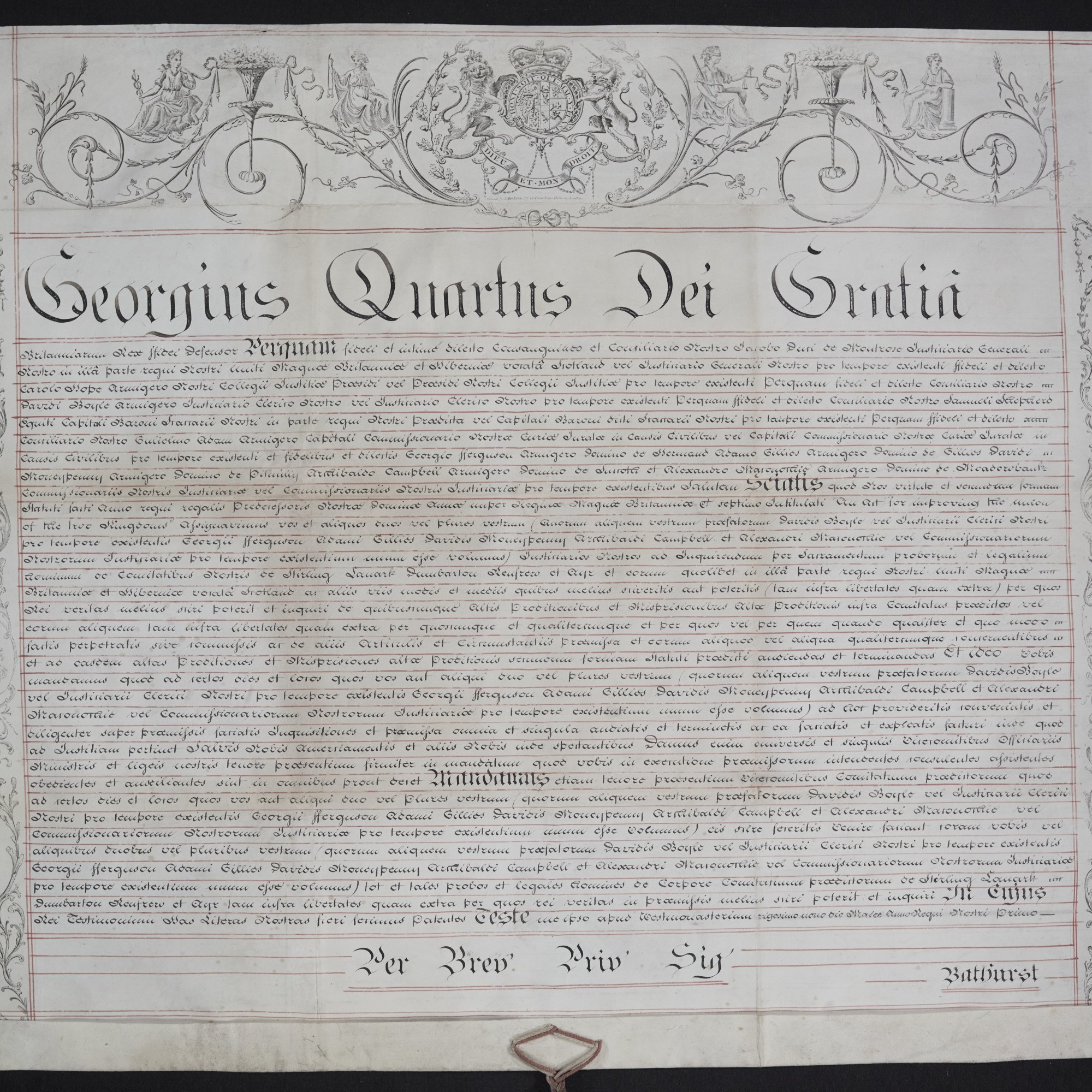

Oyer and Terminer

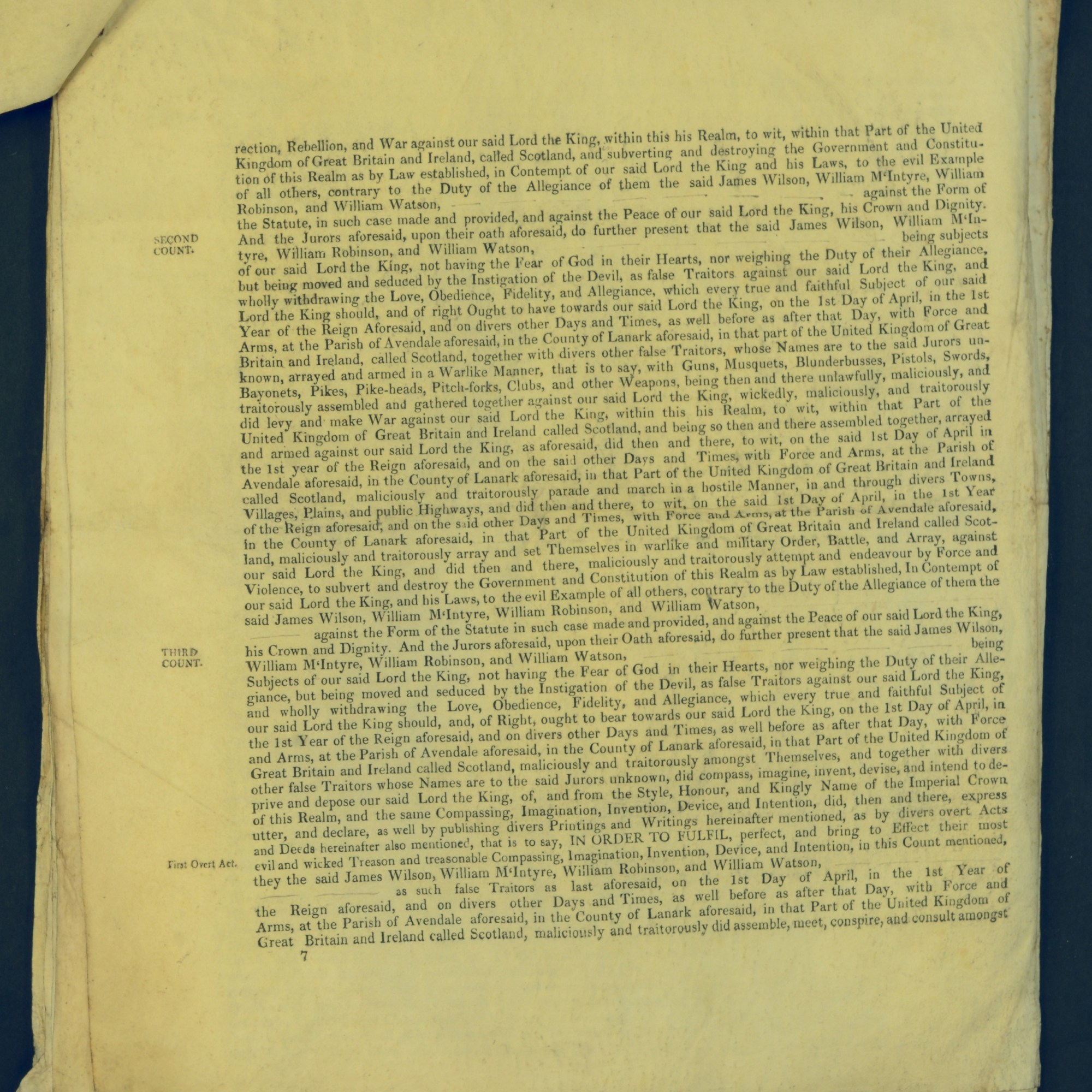

For these trials, a special commission of Oyer and Terminer was held. Although the Treaty of Union 1707 states “that all Laws in use within the Kingdom of Scotland, do, after the Union and notwithstanding thereof, remain in the same force as before”, the Treason Act of 1708 sought to unify the laws for trials of treason and misprision of treason, effectively bringing English law into the Scottish courts.

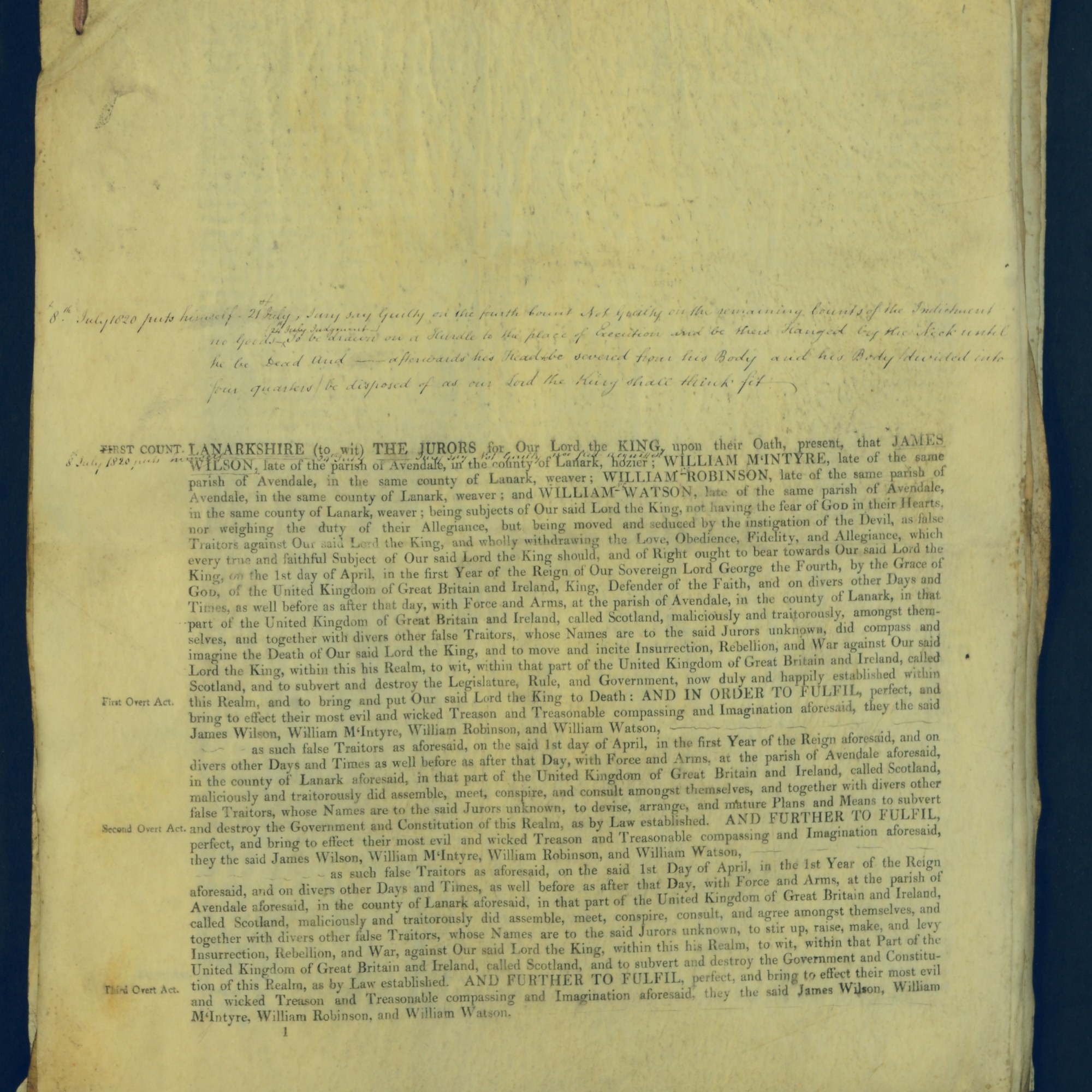

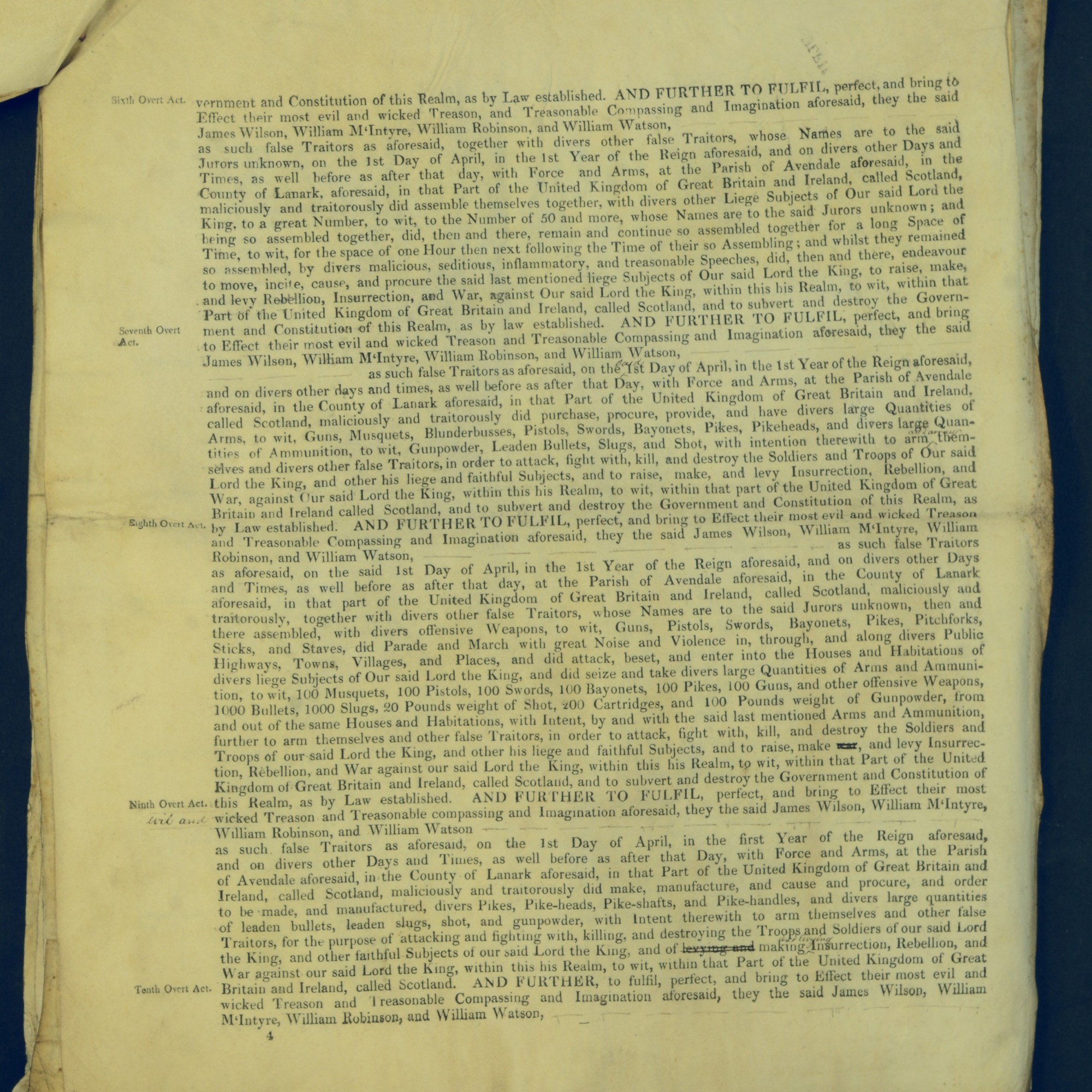

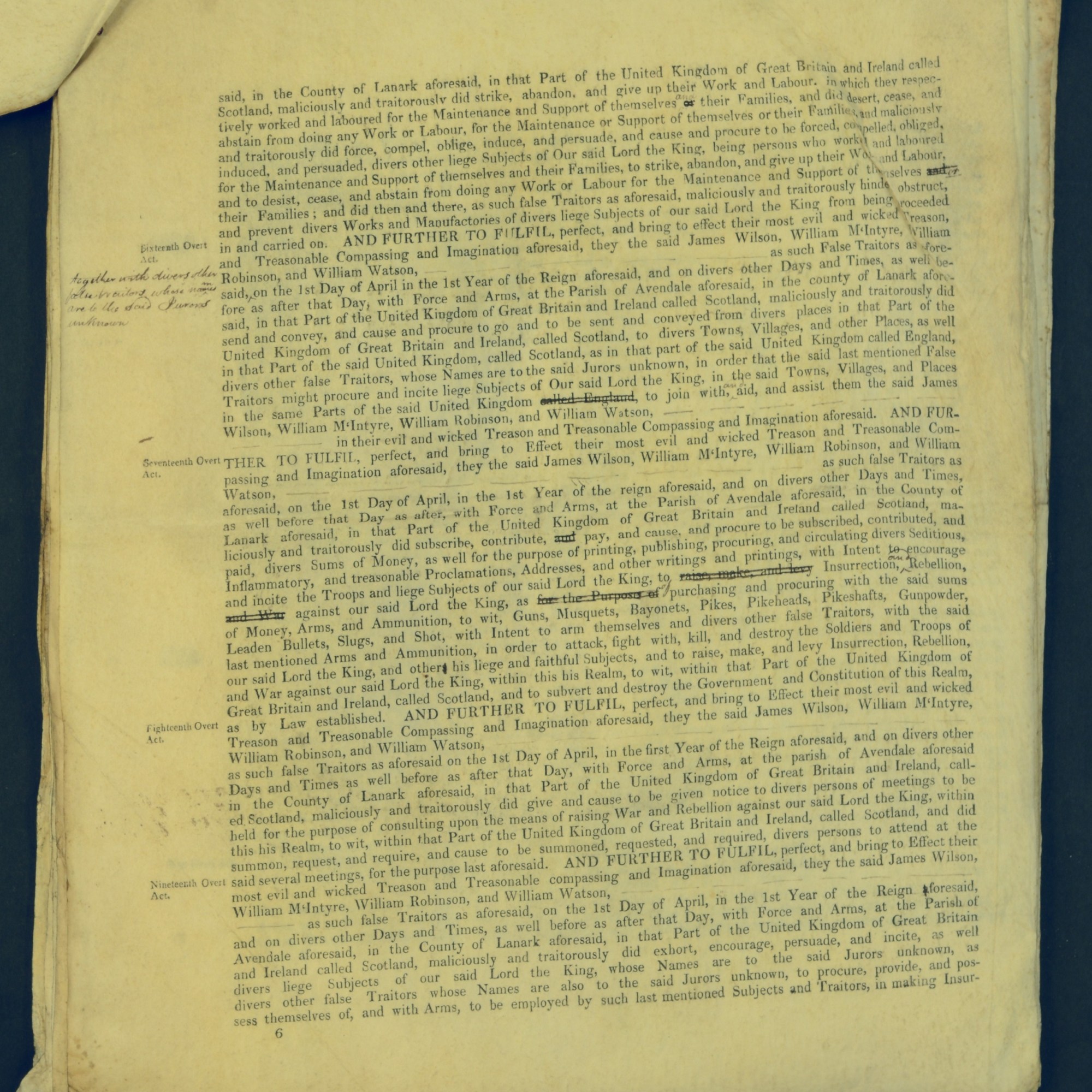

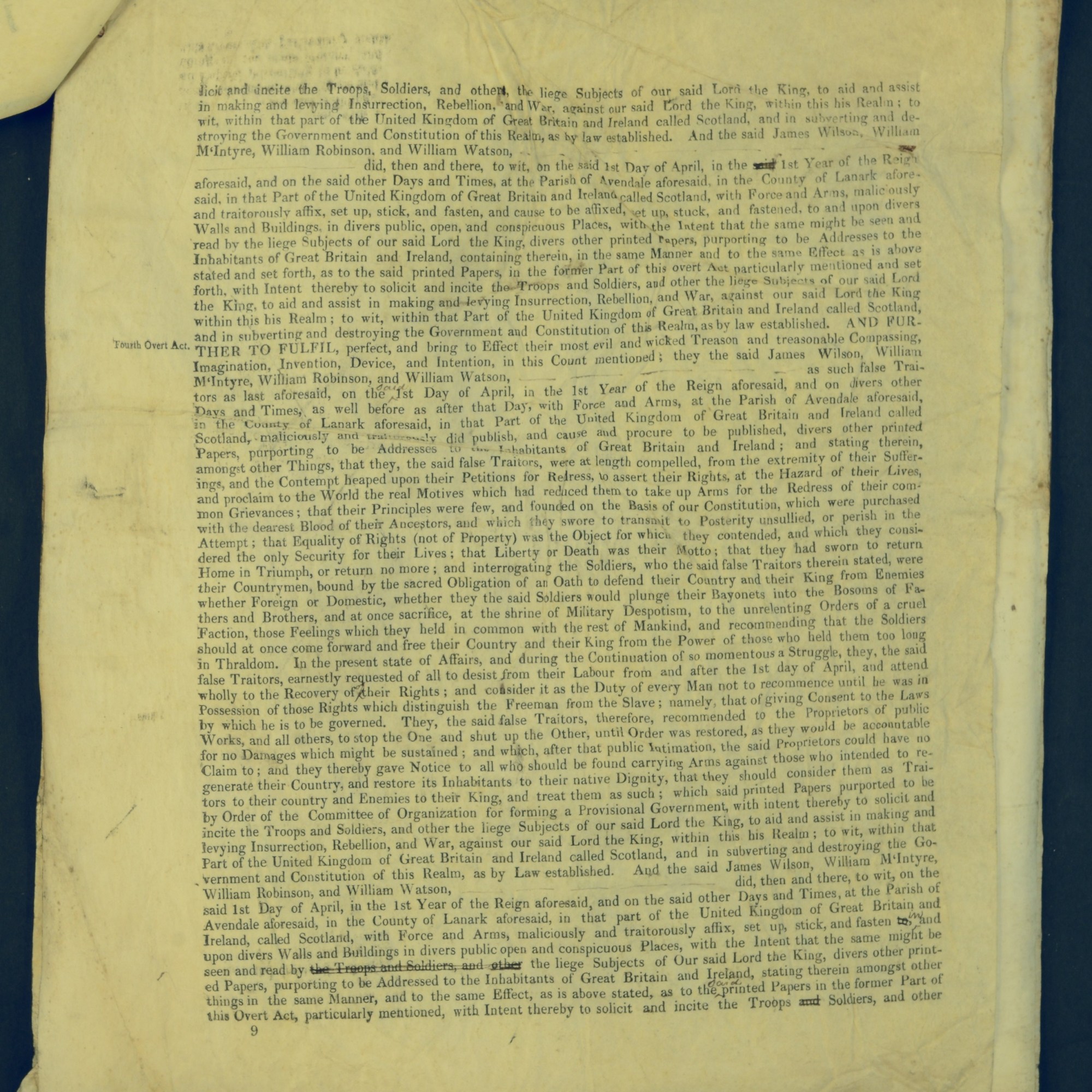

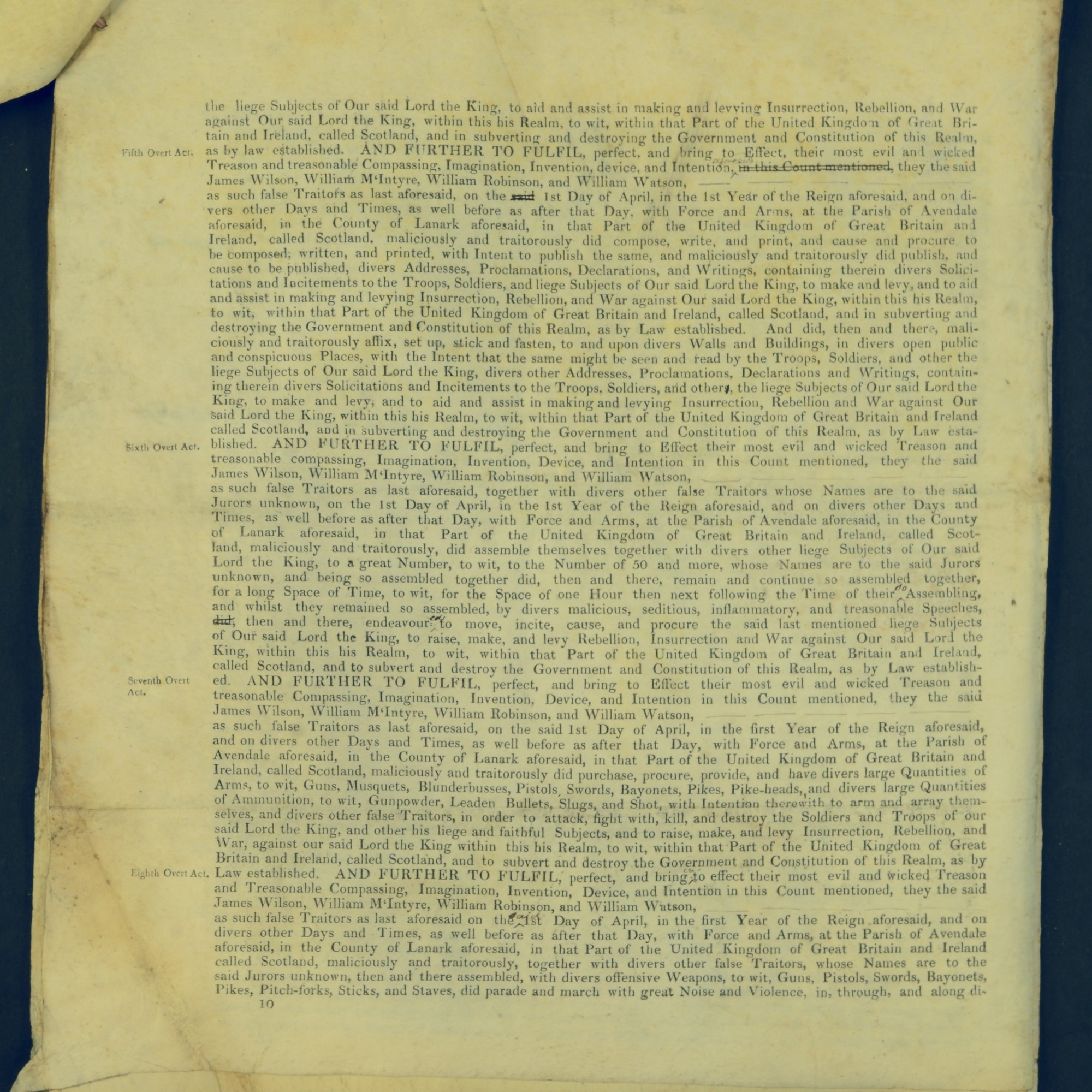

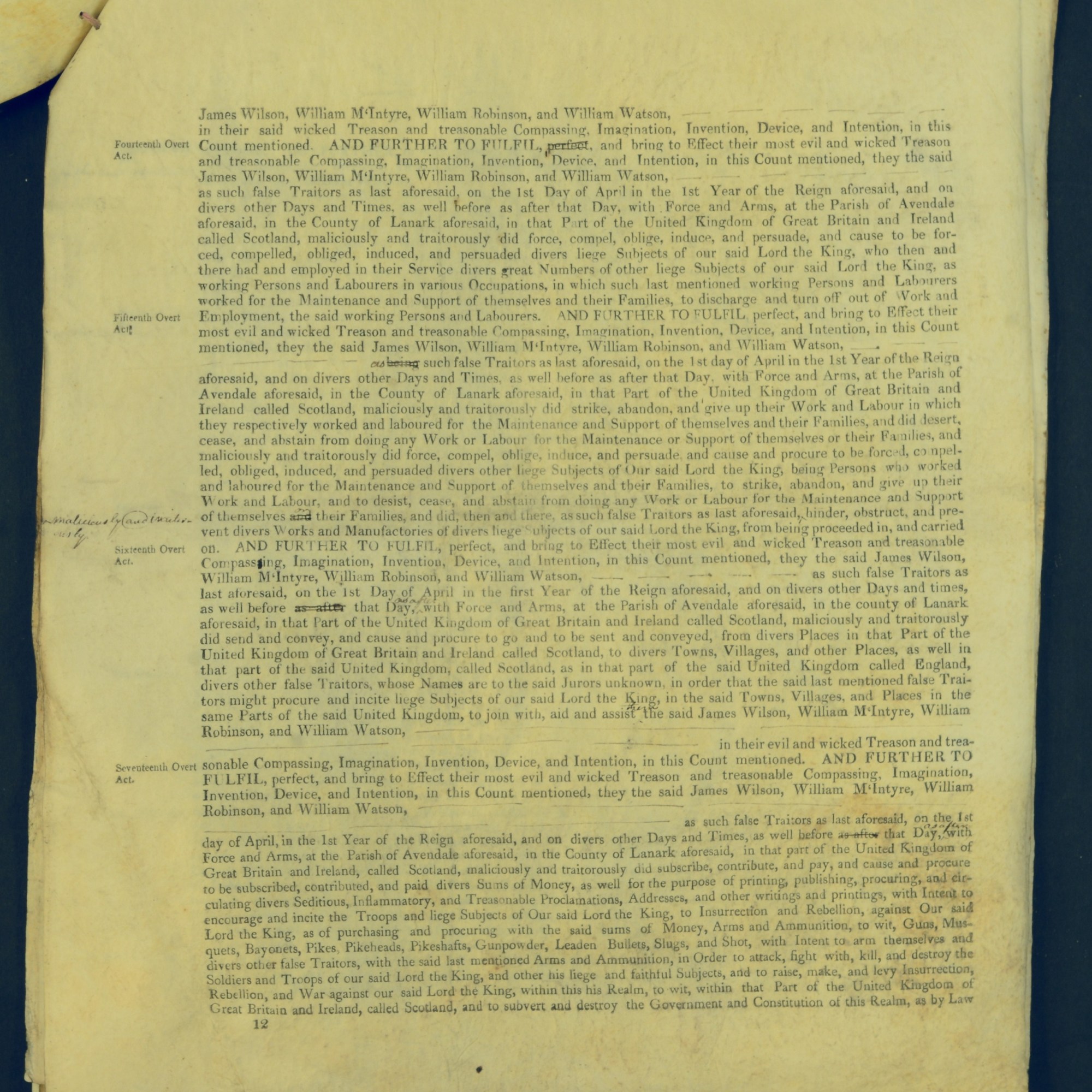

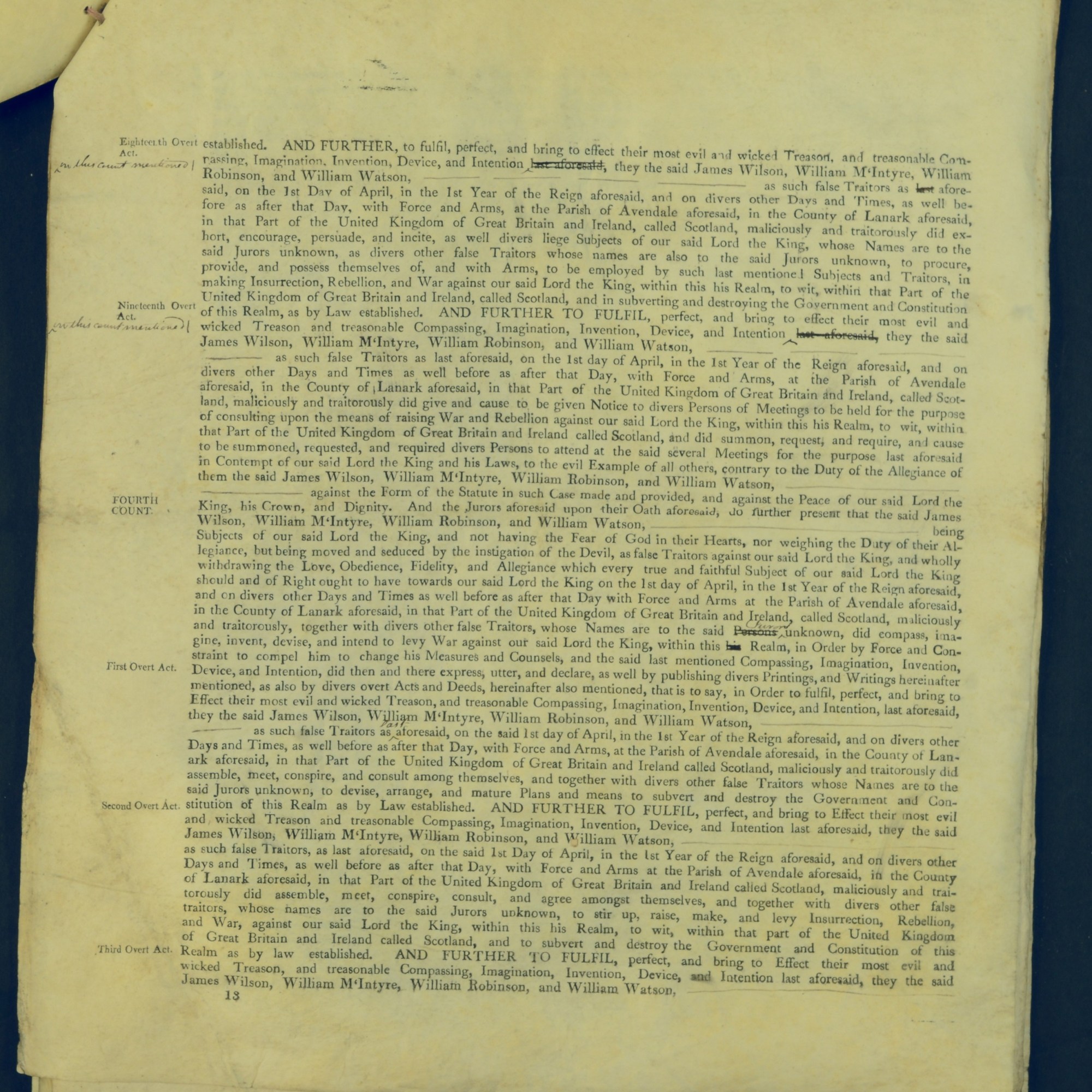

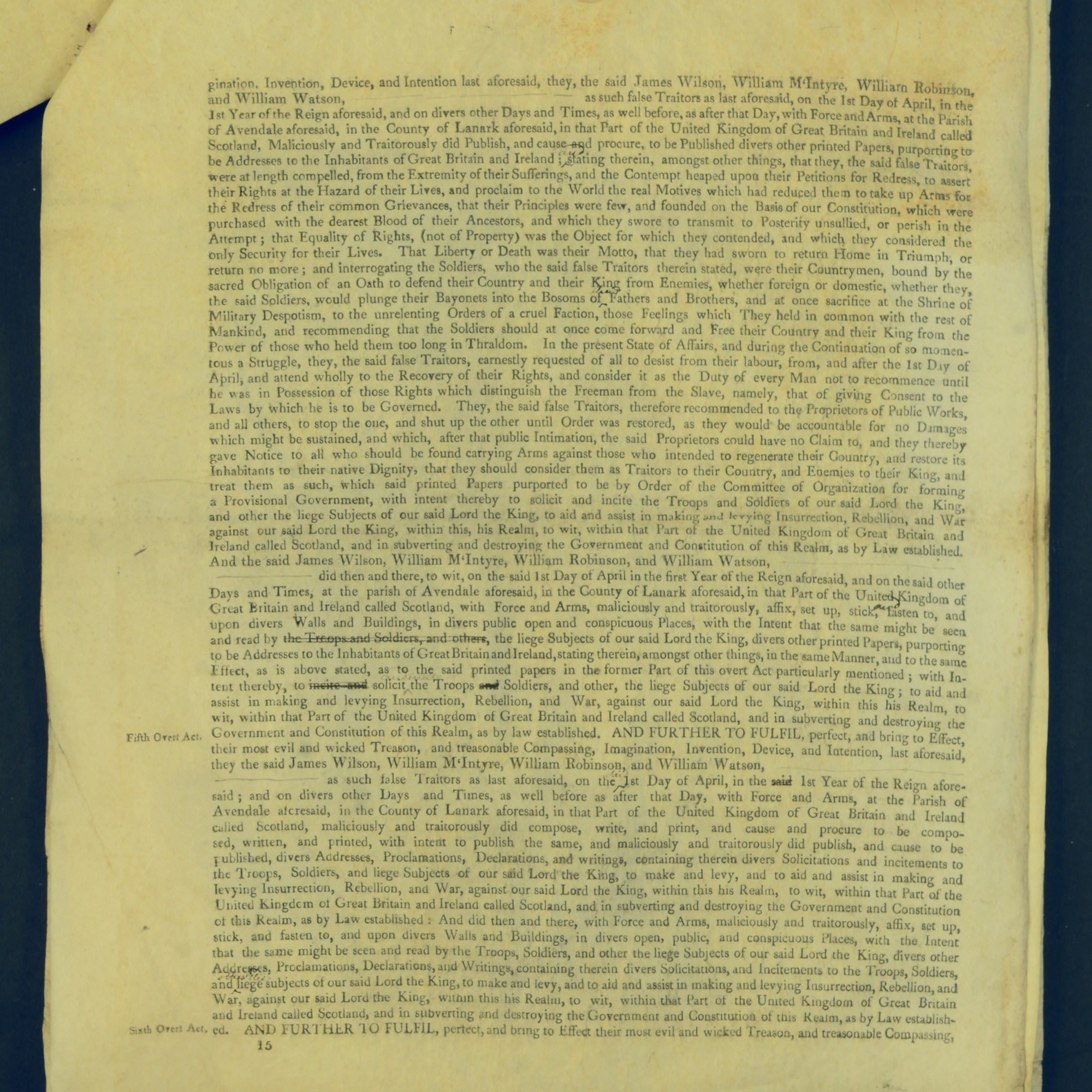

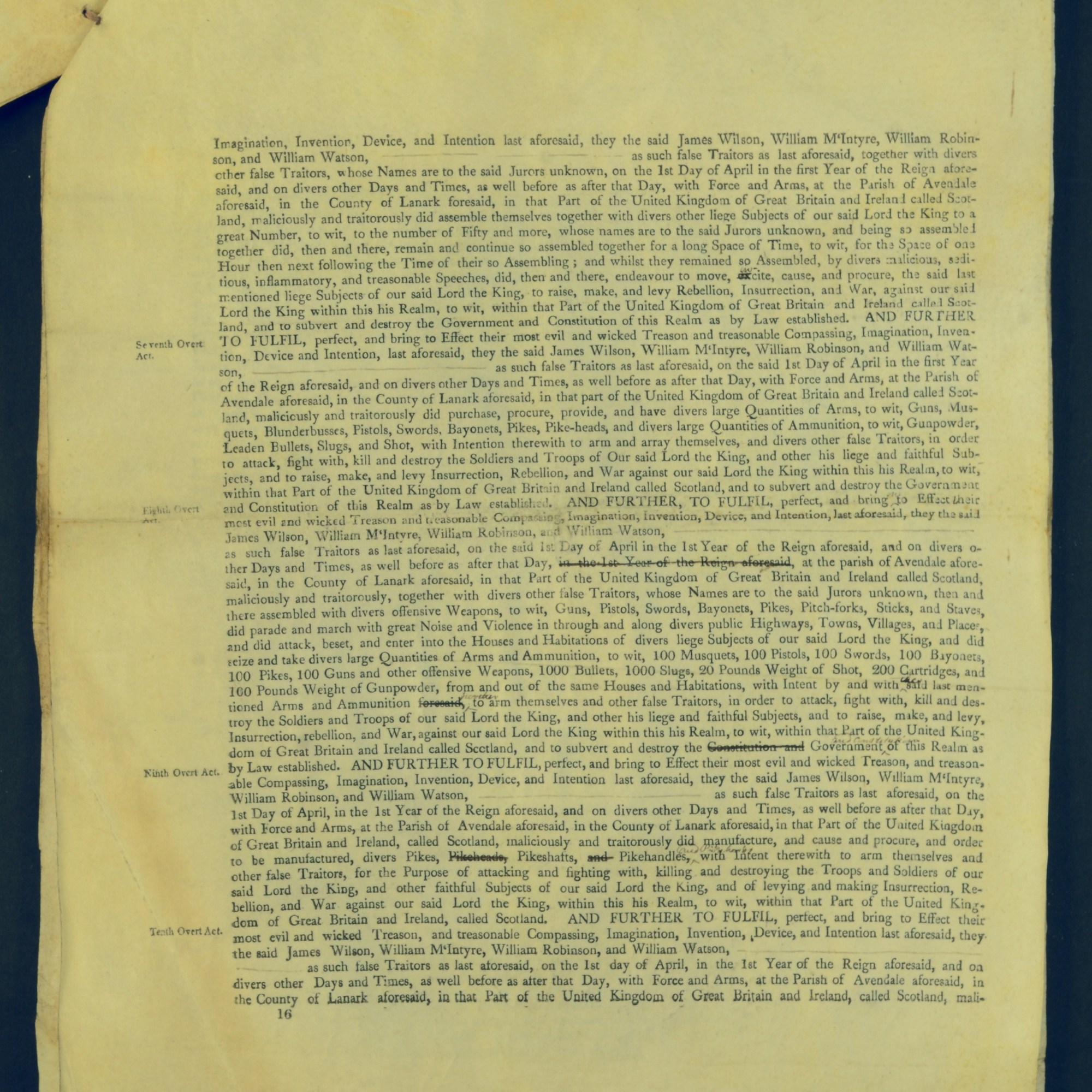

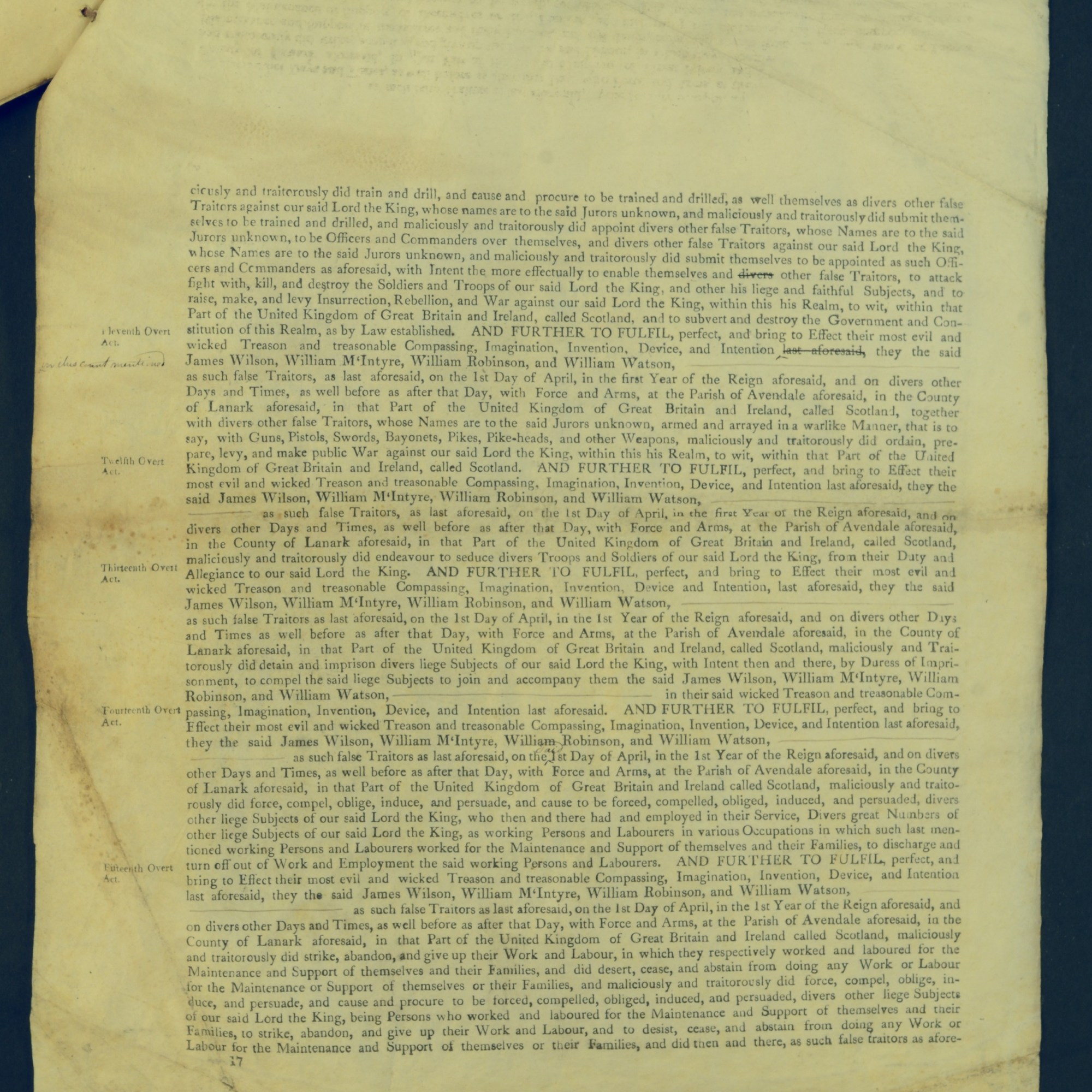

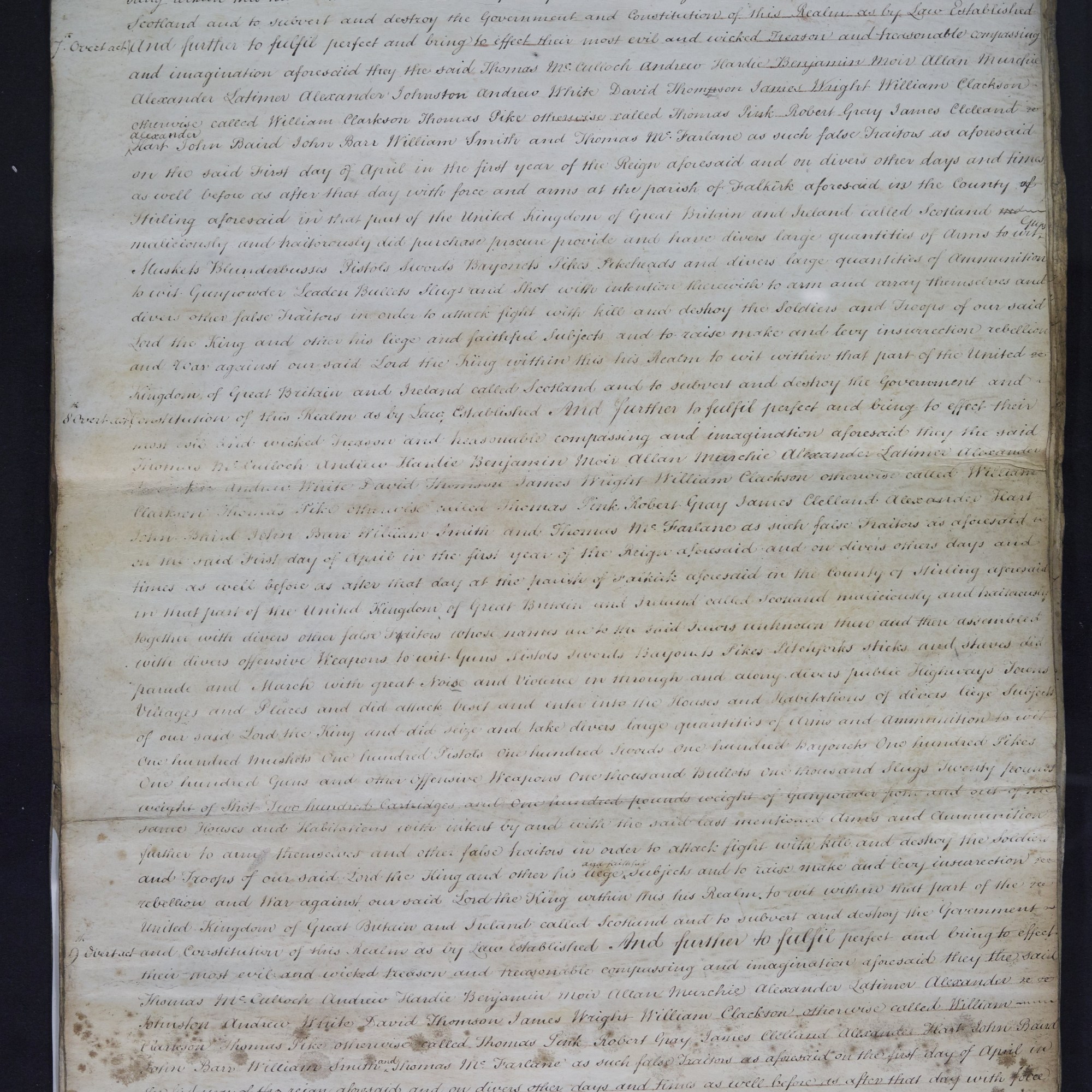

NRS holds the ‘true bills’ detailing those arrested and the four counts and 19 overt acts of treason they were charged with. The four counts were:

- for ‘compassing and imagining the death of the King, and comprehends nineteen special overt acts’

- for levying war

- for ‘compassing and imagining to put the King to death, with the same overt acts as in the first count’

- ‘compassing to levy war against the King, in order to compel him to change his measures, with the same overt acts as in the first count’

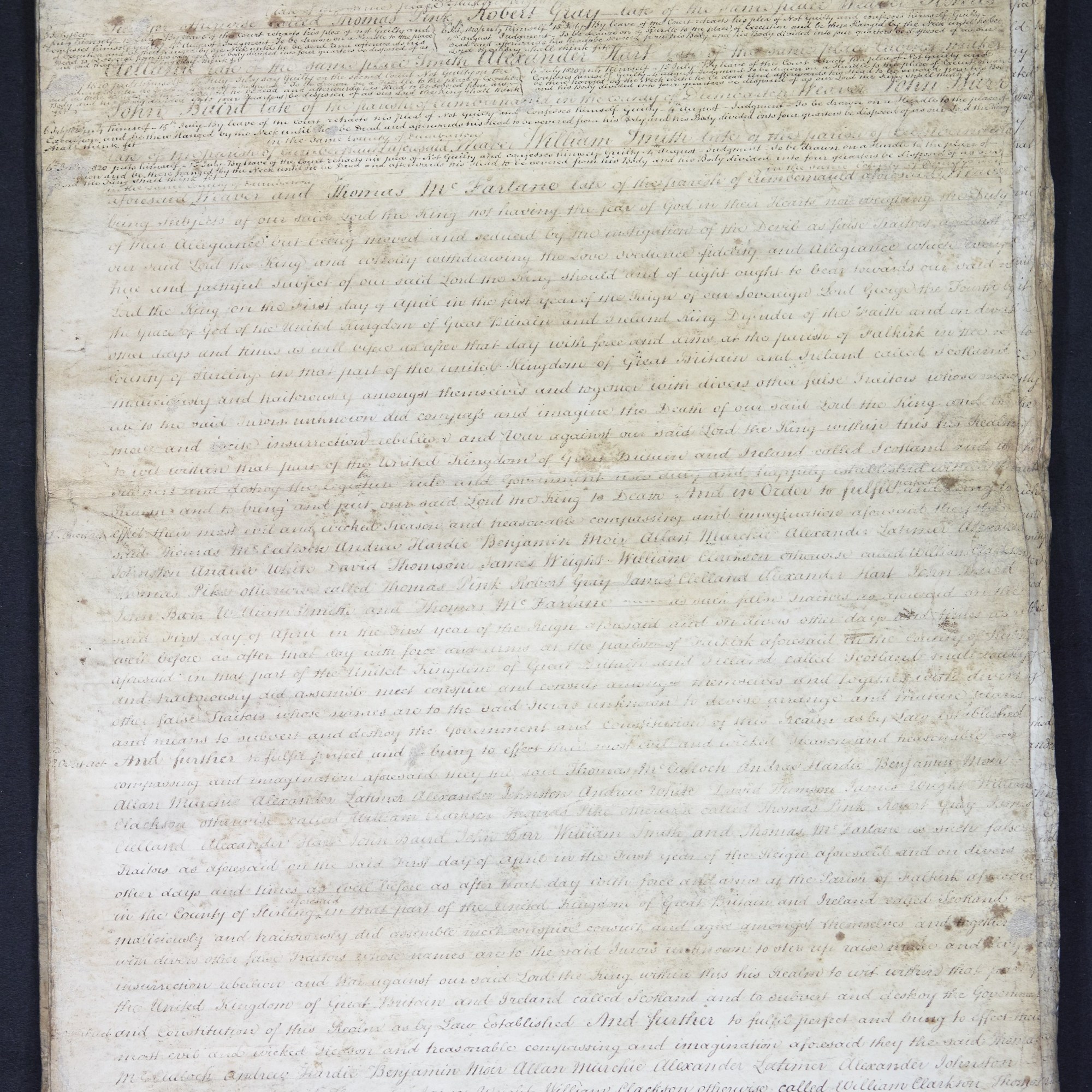

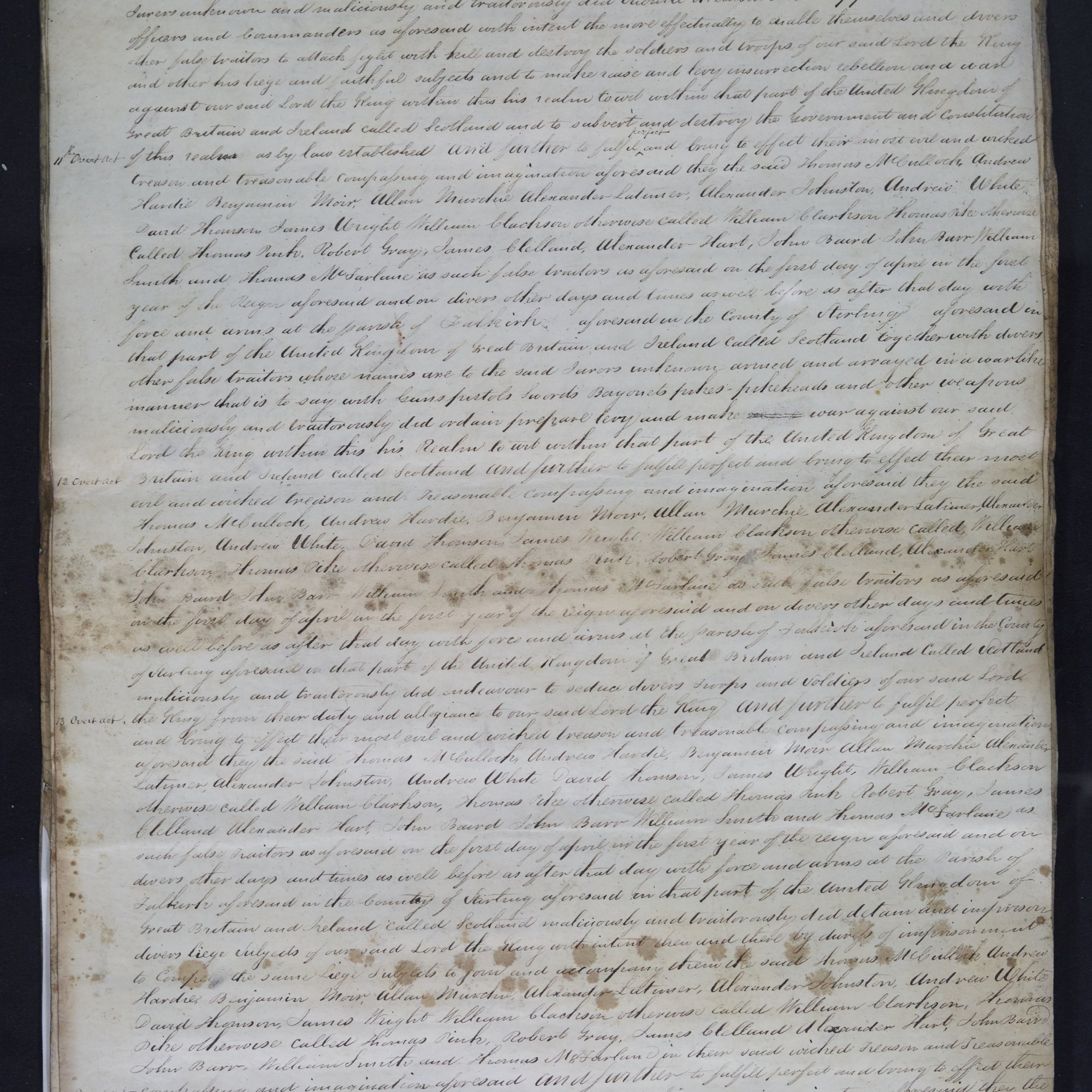

All of the prisoners were charged with these four counts; three were sentenced to death. James Wilson was tried in Glasgow on the 20th July, the jury found him not guilty on three counts, but guilty of the fourth, ‘compassing to levy war against the King in order to compel him to change his measures’.

Despite the jury’s recommendation of mercy, he was sentenced to death. Andrew Hardie and John Baird were seen as the leaders of the attempted rising at Bonnymuir, and found not guilty of counts one and three, but guilty on counts two and four. Both were sentenced to death.

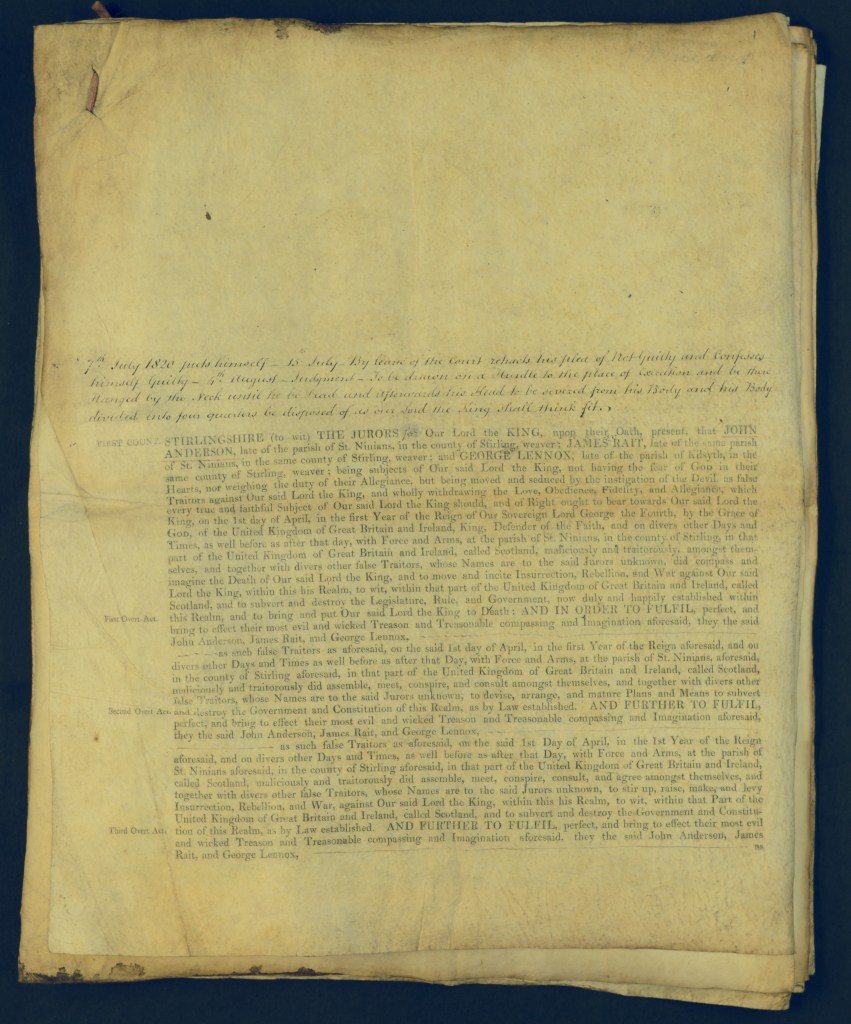

“To be drawn on a Hurdle to the place of Execution and be there Hanged by the Neck until he be Dead and afterwards his Head to be severed from his Body and his Body directed into four quarters be disposed of us our Lord the King shall think fit”

National Records of Scotland, Treason Trials, County of Stirling, JC21/2/1

Another 19 charged were transported, and it was not until 1836 that an absolute pardon was granted.

In comparison to other rebellions this attempted rising may seem like a minor event, but it is an early example of people understanding the inequality in their society and the importance of electoral representation in order to address it.

To commemorate the 200th anniversary, the trial papers held in National Records of Scotland have received conservation work and been imaged. All of the images will be available in the Historical Search Room, and a selection has been included here to show the wealth of information that can be discovered in these records.

The full descriptions for the records NRS holds can be viewed on the archive catalogue here.

Jocelyn Grant

Archivist

National Records of Scotland

My ggg grandfather William Adam, a shoemaker in Ayr, would appear to have a lucky escape after speaking at a major Radical meeting in Ayr in 1819: –

An Historical Account of the town of Ayr for the Last 50 Years, with Notable Occurrences during that time from personal recollection. Illustrated by numerous local anecdotes.” by James Howie

Chapter XI – Page 68

A great County Radical Meeting had been appointed to take place at Ayr, in order to keep up the attention of the people to Reform, and forward the cause which many had thoroughly and earnestly at heart. The meeting was held in the Back Riggs, belonging to the Crosskeys Hostelry, between Wallace Street and Limmond’s Wynd, bordering George Street and near to the Anti-Burgher place of meeting. Hustings had been erected, and every means adopted to give prominence to the speakers. Large bands of Radicals from Kilmarnock, Tarbolton, Mauchline, Stewarton, and other parts of the county, arrived at the place of meeting, in some instances considerably before the appointed hour. All the bands had banners and flags flying, on which strong revolutionary inscriptions had been placed. Their music generally consisted of drums and fifes. The party from Kilmarnock had a pole on which was elevated a cap, styled the cap of liberty,—a device borrowed probably from the French revolutionary mobs. This pole and cap was borne by a young woman, who was supported right and left by other two. The similitude between the agents employed in carrying this republican emblem consisted in nothing more than that they were females. The diabolical visages, coarse forms, vulgar speech, and brutal execrations of the continental viragos found no counterpart in the Ayrshire Radicalesses—to coin a word for the occasion ; there was nothing extraordinary in them or about them, if we except that they possessed a mind with a shade more of the masculine in it than is generally found in “Ayrshire lassies.” When all had assembled on the ground, and had clustered as closely as possible round the hustings, the delegates from the various county associations took their places on the platform, and the business began. Various resolutions were proposed and speeches delivered in their favour, all of which had a revolutionary tendency; but it was remarked, that all the speakers kept on the safe side of the law. There was nothing very brilliant in the addresses, only the commonplace sentiments and platitudes about liberty and the people’s rights ; good enough in their way, but hardly fitted to convince and convert antagonists.

During the time the meeting was being held, the militia staff were kept under arms, the yeomanry drawn out at a short distance prepared for action, and the other forces which were in the town kept in readiness lest there should be a demand made for their services, but nothing occurred to warrant their employment against the crowd. At the time the meeting was addressed by the Ayr delegate, a Mr William Adam, shoemaker, residing in George Street, Wallacetown, Sir Alexander Boswell and several of the officers of the yeomanry drew up close to the wall which divided the Riggs from George Street, and stood listening to the whole of Mr. Adam’s address. On hearing some of the remarks made, Sir Alexander observed to his brother officers that the speaker, in his opinion, was a fit subject for hanging. The remark was overheard by some persons standing near, and afterwards conveyed to Mr. Adams. That individual thought it safest to leave home for some time, and remain concealed. His premises were strictly watched night and day, that he might be apprehended, should he attempt to revisit his family; but the fugitive wisely kept out of the way till the storm blew over, when he returned to his abode in peace. As soon as the business of the meeting was over, the different parties left the ground, and took their way homewards in a quiet, orderly, and peaceable manner. The military, though held in readiness to cut down the people should the least opportunity be given to attack them, were disappointed in their expectations, and Sir Alexander Boswell did not enjoy the pleasure he is said to have promised himself a day or two before the meeting was held, of riding in Radical blood up to his bridle reins.

LikeLike