“A more hurried, nervous, frenzied place than Oban during the summer and autumn months it is difficult to conceive. People seldom stay there above a night. The old familiar faces are the resident population. The tourist no more thinks of spending a week in Oban than he thinks of spending a week in a railway station. When he arrives, his first question is after a bedroom; his second as to the hour at which the steamer from the south is expected.” (A Summer in Skye, Edinburgh 1865)’

Oban, the port town on the West Coast of Scotland in the Argyll and Bute Council area, became styled as ‘The Charing Cross of the Highlands’ in the 19th century. The name reflected its location as a crossroads to many parts of the Highlands, which resulted in it becoming a frantically busy tourist spot. Although a great number of people stayed for a night or two, on their way to a further destination, it became fashionable for families to stay for a month or longer in a local villa or lodging-house to enjoy the beautiful surroundings.

The railway, which arrived in Oban in 1880, was the vehicle for enabling people to reach the town more quickly than ever before. This article investigates how the railway transformed a small harbour town into a popular tourist destination.

The name ‘Oban’ is derived from the Gaelic word ‘an t- Òban’ meaning ‘the little bay’ or the longer version ‘an t- Òban Latharnach’ meaning ‘little bay of Lorn’ as the town skirts around a natural anchorage on the Firth of Lorn. A harbour has been established for centuries, however it began to grow as a port of trade in the 18th century. The first Custom House was established in 1765 and a distillery in 1794. In the 18th century, fishing was the town’s main industry, with small-scale shipbuilding and quarrying also supporting the local economy. In 1811 the town was raised to a burgh of barony by a royal charter.

A Scotsman, who gave his recollections about Oban at the beginning of the 19th century remembered that there was limited supplies of goods in the area; neither a butcher or baker was found in the town of around 1,000 inhabitants. He remembered that he used “to look anxiously for the arrival of Duncan Maclean, the postman, who brought a supply of loaf bread from Inveraray.”

Pigot’s Commercial Dictionary, published in 1820, recorded that there was a postal service three times weekly from Oban to the south, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays, and that the mail was carried by foot. Mail was taken to Mull twice-weekly, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Markets were held twice-yearly, in October and May.

Methods of communication, not only to and from Oban but across the Highlands, were often slow and inconsistent. Roads were narrow and in some places challengingly steep or dangerously open to the elements. Despite this, there were people with the time and means who were willing and happy to travel. The odd traveller who passed through was often welcomed readily by local inhabitants with a meal or perhaps a bed for the night. In early September 1840, Lord Cockburn, a Scottish lawyer and judge, visited Oban. There he found groups of tourists who, he said, had been drawn there ‘by scenery, curiosity, superfluous time and wealth and the fascination of [Sir Walter] Scott.’

Dr John MacCulloch, an English geologist, made a series of annual journeys to Oban between 1811 and 1821. His work, entitled ‘The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland’ (1824) is written in the form of letters to Sir Walter Scott. He describes his impression of Oban:

“This little town is neat; and if it has not thriven much since its first erection, it has at least done all that reasonable men could have expected. It adds much to the life and interest of this country, as do the shipping and boats of various kinds which are so often at anchor in its bay. There can, of course, be little employment for the people but in fishing. Yet as the rallying point of a considerable, if a scattered, tract of improved country, and of much farming on a larger scale than is usual in the Highlands, it also finds employment in the ordinary petty trades of country villages and in shop-keeping.”

By the early 19th century, a popular network of steamboat routes had been established to take tourists around lochs or islands. The Prussian architect, Karl Schinkel, arrived in Oban via horse and carriage from Inveraray. In capturing his memories of his stay in the 1820s, he described the process of a steamboat taking visitors to Staffa during the summer twice- weekly. There were also steamboats travelling between Glasgow and Oban; a journey of ten hours.

By the 1840s, railway mania was sweeping much of the central belt of Scotland and connecting large cities in a way that, a generation before, would have been unthinkable. Oban, like other localities, recognised that the absence of a railway was denying the town the opportunities afforded by the new method of transportation – namely the quicker and more affordable movement of goods and people.

However, there was an element of opposition to expanding the railway. Some people were concerned that as it cut through the countryside, the natural beauty of the space would be sacrificed in place of efficiency. They argued that, if the aesthetics were permanently scarred, the area would hold less attraction for returning visitors; if they did not like the view on their first visit, would they return?

For others, though, they were willing to allow an intrusion into the countryside to pay the price for connectivity. As historian C.E.J. Freyer notes: “Rural seclusion is all very well, but access to urban amenities is usually felt by the rurally secluded to be a good thing, and if moneyed tourists could also be persuaded to use the new route of access, so much the better. In mountain landscapes on the Scottish scale the environment is not spoiled; the railway merely becomes and unobtrusive part of it.”

In 1844 a railway was proposed to be constructed to connect Edinburgh and Glasgow with Oban on the West Coast.

This was considered ‘wild and impracticable’ at the time and there had been opposition to the route. Over the next two decades, voices were heard to question or complain against proposals to build the line. It was to cover the land of Breadalbane, passing through hilly regions, which, on a clear day, would allow the traveller to see as many as twenty Munros (summits over 3,000 feet in altitude).

The location of the station and terminus of the line was one area of disagreement. One voice was that of Mr Donald McCallum of Athol Place, Perth, who owned property in and about Oban. He was worried that the terminus would sit ‘away from the present steam boat pier, and [would be] very inconvenient in every respect of the town’. In a letter to his friend, Mr Angus Gregerson, Writer in Oban, in December 1864, he explained that ‘The traffic to and from the town has already fallen naturally into a place centrically situated and one would have thought that a Railway company desiring to provide the best accommodation for the public would have selected the same place or as near to it as they could get…I think no one can doubt that any railway which hopes to provide adequately for Oban should find a terminus as near as possible to the centre of the town and the present steamboat pier.’

By the 1860s it was clear that the railway would go ahead. A submission to make a line to Oban noted that the most direct line to Glasgow had been planned and there had been:

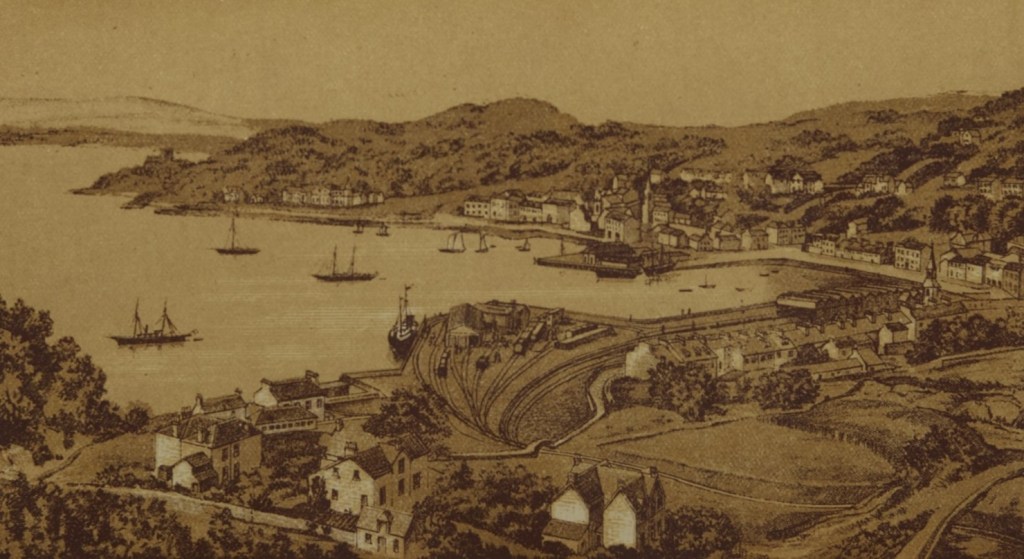

“…little difficulty in choosing Oban as the most suitable terminus for the proposed line. The large and increasing traffic between Glasgow and the West Highlands necessarily centres there, and it cannot be doubted that, with suitable railway accommodation, it will attract traffic from various parts of the kingdom. Oban is also the nearest harbour in Great Britain of any magnitude to the Continent of America; and the absence of fogs on this part of the coast is much in its favour for transatlantic communication. The Bay is of a semicircular form – has a depth of water from twelve to twenty-four fathoms – is sheltered from every wind, and affords at all times a safe refuge to ships of any burden. The harbour is of easy access, having an entrance both on the north and south. The anchorage is excellent, and it is proposed that the rails should be laid along the quays, so as to afford ready access to the shipping, and the line has been examined with this object in view.”

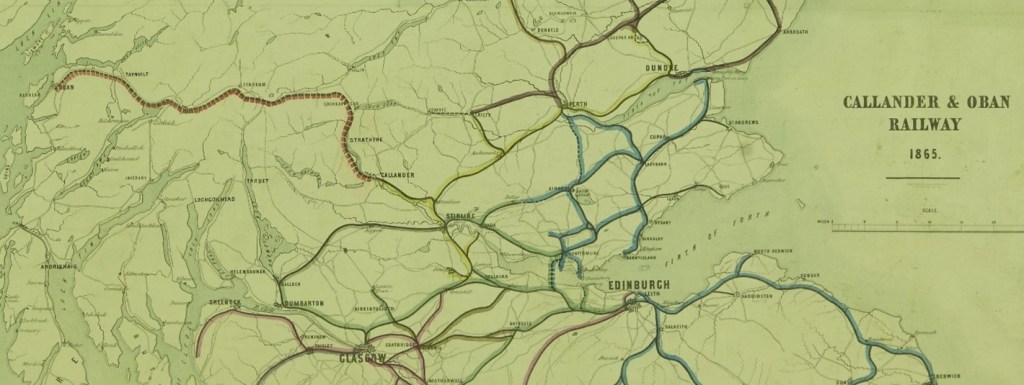

Eventually, the force of progress could not be stopped and the Callander & Oban Railway Company was formed to construct a line to Oban.

NRS, RHP965/7/1

The Authorisation Bill was introduced in 1865 and the Caledonian Railway began construction. As author Neil Caplan details, the course for this line was a challenging one. It included a severe climb up through Glen Ogle and had to traverse the difficult terrain of the Pass of Brander by Ben Cruachan. Beginning works from Callander, the first section of the Callander to Oban Railway was inspected and opened on Wednesday 1 June 1870 by Captain Tyler, Inspector of the Board of Trade. Great crowds had gathered to celebrate the moment of the first train on the line. By this date, works had been completed as far as Glenogle, a distance of 17 ¼ miles from Callander, joining the Dunblane, Doune and Callander section of the Caledonian Railway, with a new station in Callander being built behind the Dreadnaught Hotel. A lack of money forced the company to obtain Parliamentary authorisation in 1870 to abandon works beyond Tyndrum. When works re-started, lines were laid westwards from Killin and, in 1874, with a further financial investment from the Caledonian Railway, construction continued. Work then began westwards from Killin, and it took another three years to cover the 15 miles to Tyndrum. In 1874, the London & North Western Railway injected £50,000 into the Callander & Oban Railway to permit construction between Tyndrum and Oban.

By June 1880, a goods train had commenced running a trip between Oban and Dalmally. This was cause for celebration. However, due to haltering progress since 1865, the laying of the line had progressed at an average rate of 0.00005 miles an hour. In the words of C.E.J Freyer ‘a reasonably active snail could have outstripped them.’

Despite the lengthy completion time, the arrival of the line to Oban was still a cause for joy. In the wooden and glass terminal station, on the south side of the bay, a dinner was held on 30 June 1880.

NRS, BR/LIB/S/18/60/97

Tourists and travellers immediately took advantage of this new method of transport and began to flock to Oban. Beds were at a premium, but Oban rose to the challenge. George Graham, writing in his published guide book ‘Callander and Oban Railway 1880’, noted that: ‘Oban has met the want, in respect of hotels, to accommodate the immense number of tourists, and, without even moving from the Station front, ten first-class hotels may be seen.’

Visitors came from far and wide. The Oban Telegraph reported ‘a surfeit of custom’ for local shops and hotels. From May to October 1881, Oban was estimated to have witnessed 65,000 visitors. Various modes of transportation were employed but the most popular, after only one year in operation, was the railway with 37,000 visitors. Many of those had never visited the area before. In second place came the steamer with 26,000 and the stagecoach, now a rather out-dated form of transport in comparison, came last at 2,000.

In the late 1880s, ‘A Register of Oban Visitors’ was regularly captured by local publisher Thomas Boyd, who advertised local tours and excursions. All types of traveller could be spotted, including:

‘Sportsmen in knickerbockers stand in groups at their hotel doors: Frenchmen chatter and shrug their shoulders; stolid Germans smoke curiously curved meerschaum pipes, and individuals who have not a drop of Highland blood in their veins flutter about in the garb of the Gael.’

Hotels continued to be established to cater for the crowds. As historian Alastair J Durie notes:

‘by 1894, 15 hotels were open, plus numerous temperance hotels and lodging houses, some 40 in all, as against a dozen or so thirty years previously. These had been built, as one advert said, stressing the obvious, expressly for ‘summer visitors’. Some were very large; at least eight could accommodate over a hundred people. The Marine Hotel, which called itself a high-class temperance house, had 100 rooms in 1906: ‘On esplanade. Magnificent sea-view. Moderate tariff.’

NRS, BR/TT/S/3/2/10

Today, Oban is still a popular tourist destination, being accessible by road, air, bus, sea, bicycle and, of course, the train with a number of ScotRail trains running between Oban Railway Station and Glasgow Queen Street each day. The direct route to Edinburgh closed in 1965 and the services north to Ballachulish on Loch Leven were withdrawn in 1966 due to changes known as ‘the Beeching cuts’ as part of the restructuring of the nationalised railway system in Great Britain in the 1960s. Despite this, visitors still enjoy the beauty and heritage of the town in the same way that their Victorian predecessors did throughout the 1800s.

Scots on the Move: Railways and Tourism in Victorian Scotland, a free exhibition, runs in the Adam Dome, General Register House, 4 August-26 September 2025. It tells the story of the ways in which the introduction and expansion of the railway changed travel and tourism forever. Open Monday to Friday, 09:00 – 16:00.

Veronica Schreuder

Archivist

National Records of Scotland

Resources used/further reading

Alastair J. Durie, Scotland for the holidays. Tourism in Scotland c1780-1939.’ (2003).

George Mackay, ‘Scottish Place Names’ (2000)

Webster’s Topographical Dictionary of Scotland, (1819)George Graham’s own copy of privately published guide book entitled ‘Callander and Oban Railway 1880’. GD1/1160/160.

Oban Times and Argyllshire Advertiser, Saturday 3 February 1917

C.E.J Fryer, The Callander and Oban Railway (1989),

Oban Times and Argyllshire Advertiser, Saturday 26 June 1880

Letters relating to objections to the proposed Oban railway, NRS, GD112/53/68/1-2

David Ross Getting the Train. The History of Scotland’s Railways (2017)

Neil Caplan, Railway World Special, The West Highland Lines (1988)