Digital Imaging Specialist Clare Stubbs delves into the archives to learn more about Morison’s Haven, a once-thriving port at Prestonpans in East Lothian, now long deserted.

For people travelling from Edinburgh to North Berwick along the curving lines of the East Lothian coast, there are hints of its industrial history dotted along the landscape. One of the most dramatic sites is the Mining Museum at the old colliery at Prestongrange.

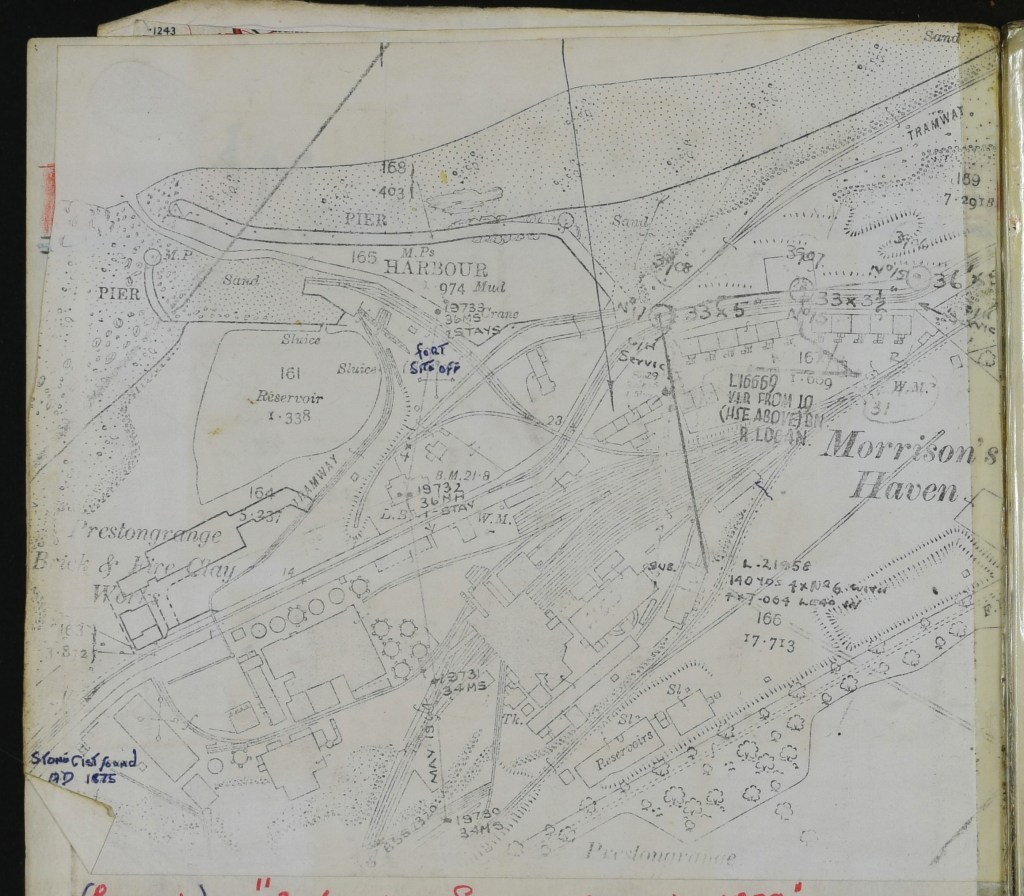

On the shoreline directly opposite the former colliery, a large solitary round balustrade stands in the middle of the rocky beach. With no context around it, it looks strange and out of place, but this is almost all that remains of the busy and bustling port of Morison’s Haven.

For centuries, the harbour was a pivotal part of the life of the surrounding area, especially for the nearest town of Prestonpans, which had been a centre of industry since the 12th century.

Kings and noblemen granted lands to the monks of Holyrood and Newbattle Abbeys, leading to the area being named ‘Priest-town’. They also took full advantage of their position to open the first salt pans of the area, adding the ‘pans’ to the town’s name, and opening the first coal mines to keep the pan fires burning.

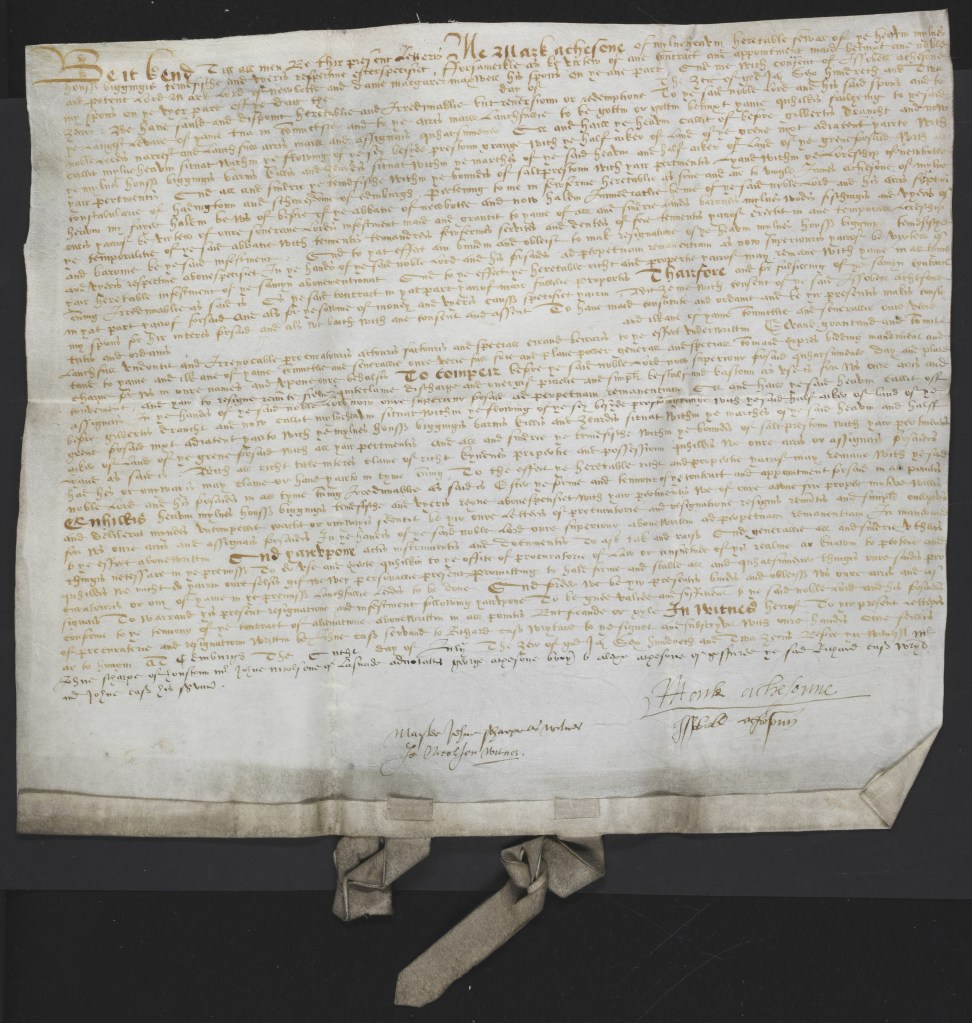

By the 1250s, the monks had accumulated several mills as well as acres of land, the salt pans and the mines in the area. While there may have been a small port there at the time, the first official mention of a harbour being built was in 1526, when a royal charter was granted to Newbattle Abbey.

Initially named Gilbertis Draucht – the ‘is’ ending here representing possession, so in a modern sense ‘Gilbert’s’ and Draucht, meaning ‘the process of drawing water from a stream or land; a channel made for this purpose’ (https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/draucht) – the harbour went through a succession of names depending on ownership and function. One of the earliest was Mylnehevin or Milnehaven, probably so-named for the tidal mills that were recorded there in 1603. It passed into the hands of the Acheson family who managed the customs duties for the area and eventually to the Morisons of Prestongrange in 1609, from whom the long-standing name was derived. The spelling of the name can vary, but it is now more frequently spelt, ‘Morrison’s Haven’.

In the 17th century, the area was on the rise with the expansion of industry and business flourishing. Numerous families were connected to the local salt pans with disputes over management and control of the income recorded (see GD220/6/1870, GD150/1470), especially since the new harbour allowed for the export of the salt and other products to mainland Europe and Scandinavia.

In the 1620s and 30s, further industries started to appear. This briefly included glassworks, which were referenced in the Privy Council records in 1625, ‘about Prestoun Panis and Aichesonis Haven, alias callit Newhaven, and in speciall to the people attending the glassworkis thair’ [sic].

With the surge in international trade, Morison’s Haven became a significant customs port throughout the 17th century, covering a vast stretch of the coast. Import and export books show ships arriving from all over Europe including various Scandinavian ports, Danzig (Gdansk) in Poland, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal. Imports also arrived via London, bringing exotic trade goods from further afield including the increasingly popular tobacco, sugar, indigo and ginger from the Americas, Caribbean and Asia.

Imports included fresh fruits such as ‘oringes and limons’ and various regional alcoholic products including French and Portuguese wines, Danzig water and brandy. Specialist items such as drinking glasses, pins and needles, soap and particular types of oil also arrived in huge quantities. Other primary imports included raw materials such as wood from Scandinavia, hemp and alum as well as copper and iron from mainland Europe.

Outbound ships left carrying the usual supplies of salt and coal, but Prestonpans was expanding with oysters dispatched as far as Latvia, lobsters to London, barrels of eggs to Sunderland and locally produced beers dispatched up and down the coast.

To take full advantage of these trade routes, dozens of earthen works sprang up in Prestonpans, using the good quality clay in the local soil and the ready access to coal for the furnaces. They produced everything from dishes and pots to tiles, pipes and bricks.

From around 1696, William Morison – with support from financial partners – decided to resurrect an industry not seen in the area for decades: glass manufacture. The location was perfect for it with all necessary raw materials including coal and good quality sand, close to the main roads to Edinburgh and a port available for shipping.

Glasshouses and furnaces were constructed close to Morison’s Haven with Morison “bringing home from abroad expert Workmen for the said work”. The primary products were bottles “sold at very moderat and easie Rates” but in addition, they started to produce “several other Sorts and Species of Glasses, which were never heretofore Manufactured within this Kingdom”. The array of products included glass for mirrors, spectacles, carriages, lamps, watches, windows, and special moulded glass.

After two years of preparation, all his investment paid off. After seeing examples of the glasswork, the Privy Council issued an act in 1698 which “prohibits all persons whatsomever (except the said William Morison of Preston Grange, and his Co-partners) from making any of these new Species of Glasses” (from the ‘Act and ratification in favour of the Glass Manufactory at Morisons Haven’, National Records of Scotland, GD109/3945).

Unfortunately for William Morison, the glassworks were not as financially viable as he hoped and within a few years they shut down as Morison fell into increasing debt.

Industrial Expansion

As well as increased trade in goods, breweries stretched the length of Prestonpans, producing for both a local market and an international one. In a time when fresh water could be a health hazard, beer was a standard drink for people of all classes and – at their peak – there were at least 16 breweries in Prestonpans.

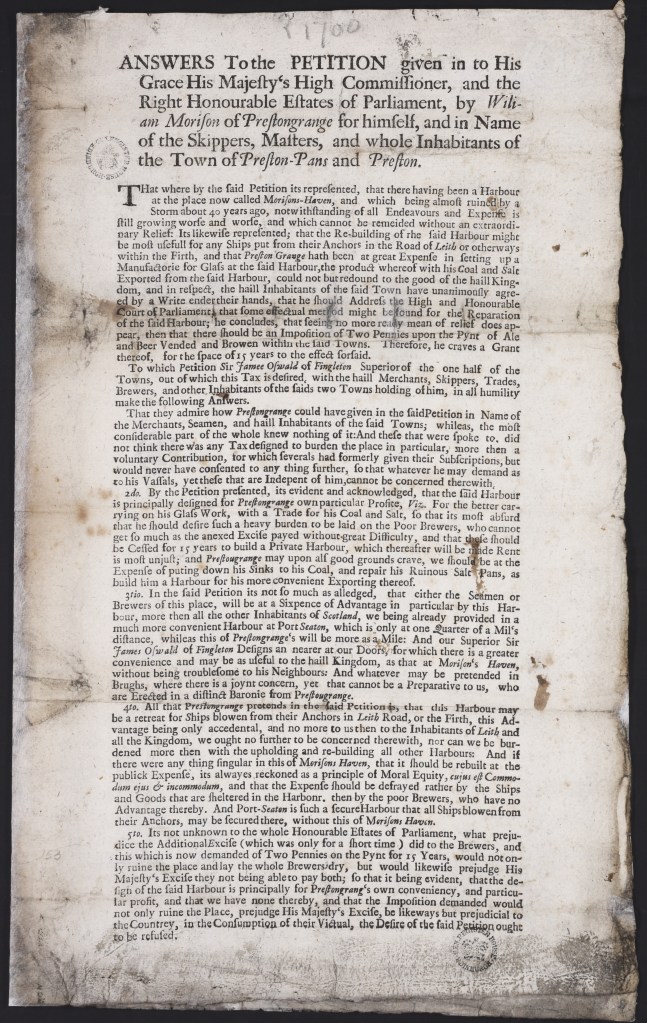

These breweries were dragged into a campaign by William Morison to refinance the repairs of the harbour with additional taxation in 1707. According to Morison, a storm had caused substantial damage and he called on the Privy council to allow additional excise charges on beer with a supporting petition of the brewers of the town.

The petition was rejected as the council stated “it is evident and acknowledged, that the said Harbour is principally designed for Prestongrange own particular Profite… so that its most absurd that he should desire such a heavy burden to be laid on Poor Brewers” and suggested that the brewers make use of the nearby harbour at Port Seton instead.

A few years later, Morison sold Prestongrange and the associated lands, but industry continued to flourish. The harbour provided a new fishing port and the local and imported raw materials allowed expansion into new kinds of business such as soap and quicklime production.

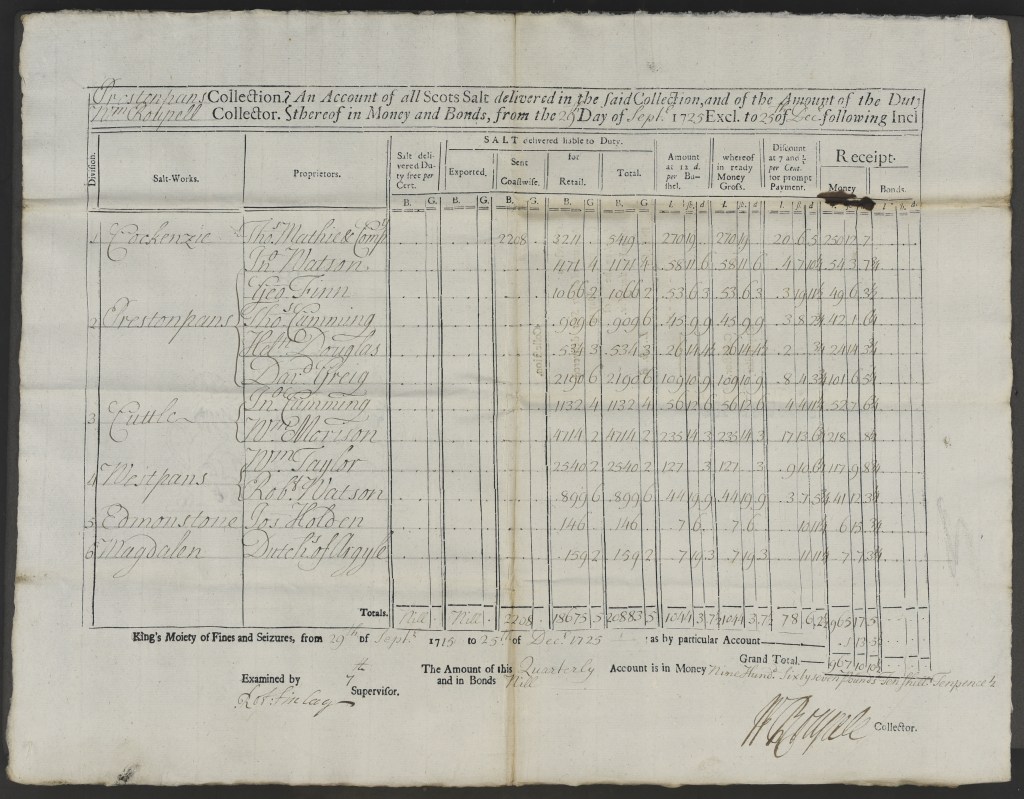

Though the glassworks were gone, the pans, mines and earth works thrived. Despite the imposition of a salt tax after the Act of Union, the salt-pans worked constantly. By the 1720s, the Prestonpans salt works produced tens of thousands of bushels of salt per quarter. Between 29th September and 25th December 1725 alone, the local pans produced 20,883 bushels of salt – over 600 tonnes.

Meanwhile, the repurposed furnaces and kilns were used by potters and their goods were exported all over the world, while more specialised workshops were built in West Pans to produce high-end fine china.

More brick and tile works expanded around the harbour as well as forays into iron-work. The tidal mills were still functioning but instead of grinding meal as they had in the past, they were also used to grind up flint to be used as glazes by the potters.

Look out for Morison’s Haven – Part 2, to find out more about the area and its history.

Clare Stubbs

Digital Imaging Specialist

Very interested to learn that the numerous (dozens?) of earthenware potteries in the vicinity “exported their goods all over the world” from Morison’s Haven. Do you know precisely who the manufacturers were, and which destinations were their primary export targets?

LikeLike

Hi there: I asked the author of this article if she had any further info, and she’s given me the following…

“In the 1820s onwards, Belfield & Co. were one of the biggest producers – the Prestongrange official site has a PDF article with some pretty spectacular examples of their work. They were famous for their colourful glazed pots and dishes, even a collection of decorative spittoons.

“Between the 1740s and the early 1900s, the big four potteries were at various points Belfield, Gordon’s in either Bankfoot/Morison’s haven depending on the year (we have one of their receipts with an image of Morison’s haven on it- GD6/1294/3), Watson’s in the west side of Prestonpans, Cadell’s in Kirk Street and the main Westpans pottery.

“Robert Bagnall & Company is another one working out of Westpans, as well as Hamilton Watson who produced earthenware, and I’ve seen mention of at least one unnamed pottery based at Cuthill, the industrial residential area between Morison’s Haven and Prestonpans itself. Other smaller works were scattered around the town as well, including Rombach and Cubie, who both had a single kiln.

“We have the names of a lot of individual potters who ended up caught up in legal incidents between the 1740s and 1900s as well, plus a large number of sequestrations and various financial upsets for the big companies too.

“Regarding the export targets, it’s harder to say. While there is evidence that earthenware from Prestonpans/Prestongrange ended up in America, no ships from Morison’s Haven ever made that journey directly. As with the imports from the Caribbean, America and Asia, a lot of the non-perishable exports would have gone via London.”

Hope that’s helpful!

LikeLike