Before the foundation of Waverley station, the north side of Edinburgh’s old town looked very different. For nearly 400 years, the Trinity Collegiate Church was a stalwart feature of the Edinburgh city landscape.

Some 19th century writers claimed that James II was also responsible for the founding of the church, but a Papal Bull indicates that the church was founded by Marie of Gueldres, in memory of her husband. No evidence for the 19th century claims has thus far been found.

per charissimam in Christo filiam Mariam clare memorie Jacobi Secundi Scotorum Regis Relictam viduam insignis Collegiata ecclesia sive capella aut Hospitale pauperum Sancte Trinitatis extra oppidum regium de Edinburgh Sancti Andree diocesis fundata

Transcript of Papal Bull of Pius II (circa 1463)

The church was established on the north side of the city in the low ground beside Calton Hill. Gordon’s engraved survey of the city of Edinburgh from 1647 shows the church adjoining the Leith Wynd port (gate).

As a collegiate church, it was managed by a provost, eight chaplains – or prebendaries – and two choristers. The adjoining hospital on the grounds also provided support for 13 poor persons – or bedemen.

Mary of Guelders died in 1463 and upon the completion of the Trinity kirk, she was later interred in the church that she had founded. During the church’s demolition, two skeletons – one of which was believed to be that of the late queen – were removed and re-interred in Holyrood abbey.

The church itself was never finished to the original cross-church design: only the choir, aisles and transept were completed with a porch and a chantry chapel.

All the same, it was still an impressive example of Medieval architecture with elegant lines, decorative windows and ornamentation.

An altarpiece commissioned for the church was painted by the Dutch artist Hugo van der Goes in the 1470s and it was considered one of the most significant altarpieces painted for a Scottish chapel. Removed from the church and into the Royal collection by at least the 17th century, the remaining panels can now be seen in the National Galleries of Scotland.

During the reformation, the Trinity church was – as with many churches in Scotland – turned from a Catholic institution to a Protestant one. In 1567, James IV issued a decree placing the buildings surrounding the church into the charge of Sir Simon Preston, the Provost of Edinburgh. He subsequently gifted it to the city, asking that the buildings serve as a hospital for the poor and needy.

In 1574, the Actum de reformation communis sigilli Collegii was written up and “the provest and prebendaris underwritten have and respect to the reformatioun of the religioun and abolessing of idolattrie haue thocht expedient that their common sele of the said college be their common consent that their chaptoure be changit and reformit” [SIC].

Religious imagery “efter the auld manner” was removed from the church, replaced with text and the royal coat of arms. It is believed this is when the missing panel of the van der Goes altarpiece – which likely contained an image of the holy trinity – was lost.

As time went on and the city expanded to fit the ever growing population. By the late 18th century, a grand new town was in the process of being built. This included a broad new bridge – now the North Bridge – that extended over the grounds of the kirk, connecting the old town with the new.

The Trinity Church saw even more of this growth up-close: to the north of the kirk’s grounds, a large orphanage was erected and in the 18th century and a small chapel was founded by Lady Glenorchy within the grounds of the kirk for the betterment of the poor in the city.

By the 19th century, an industrial revolution had come to the city. The Union canal between Glasgow and Edinburgh brought new transit links to the city in the early 1820s. By the 1830s, rail transport was rising in demand with rail links being built up and down the country.

In the 1840s, the North British Railways company’s line from Glasgow to Edinburgh ended at Haymarket, but they wanted to expand their operation, creating a more central connection hub between the east and west coasts.

In order to progress with the expansion of the railway lines, they approached Parliament. In 1844, an Act of Parliament authorised the plans:

“And be it Enacted, That, subject to the provisions and restrictions in this Act contained, it shall be lawful for the said Company, and they are hereby empowered, to extend the line of the said railway, and to make and maintain such extended line of railway, with all proper depots, warehouses, works, approaches and conveniences connected therewith, from the present terminus of the said railway, at the Haymarket, in the city of Edinburgh, through the following parishes, viz. St Cuthbert’s, St George’s, Tolbooth, Canongate, High Church, St Andrew’s, Trinity College, and Lady Glenorchy’s Church parish, or some of them, to and to terminate at or near the North Bridge in said city, upon, across, under or over the lands delineated and described on the plan and in the book of reference hereinafter mentioned, and for that purpose to enter upon, take, purchase, and use such lands of so delineated and described as shall be necessary for making and constructing the said railway and the other works and conveniences.”

[BR/AP/S/25]

Over the next few months, the Kirk session of the church noted disruption and problems caused by the railway works. In 1845, concerns were raised about the fact the station elevation around the church would interfere with access to the building itself.

Formal letters of complaint were submitted to the Lord Provost and council about the “encroachment made and being made by the North British Railway Company on the property of the Church”.

In December of 1845, the kirk session received a letter from “the British Railway Company, intimating that they meant to apply to Parliament for power to remove the Trinity College Church” and resolved to prevent “the demolition of the present Parish Church at all events till another suitable & permanent edifice has been provided by the said Railway Company”. [CH2/141/14]

The Society of Antiquaries for Scotland wrote to appeal to the Queen the request her intervention “or to direct the Queen’s Architect for Scotland to report to your lordships on the most effectual mode of preserving this venerable edifice”. [CR4/174]

In 1848, an act of Parliament led to the closure of the church on the guarantee of “its restoration in the same style of architecture” as “ample funds were assigned to the Town Council of Edinburgh by the North British Railway Company” for the purpose. [CH2/141/15]

Rather than demolish the church, the whole building was taken apart stone by stone, pieces of it numbered and stored on Calton Hill until a decision was made about the new location for it to be rebuilt.

The congregation of the church moved through various rented locations for over 20 years. In July of 1871, the moderators were still pursuing the council “to have the new church built in Chalmer’s Close” because “the good of the parish and congregation are seriously hampered by the inconvenience of their present place of worship” [CH2/141/16]

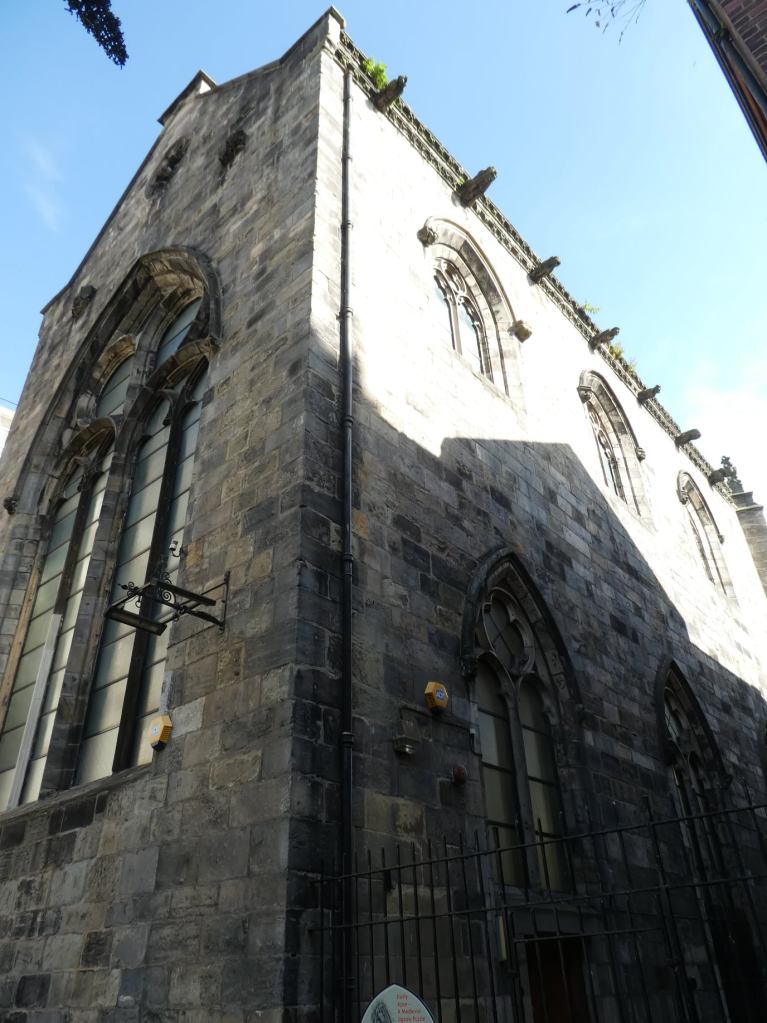

By the time rebuilding began in 1872, so much of the stonework had been removed or acquired for building works that they could only rebuild a small portion of the original church. What remained was rebuilt in Chalmers Close, just off Jeffrey Street, as part of the new church, barely 300 feet from where it originally stood.

The new Trinity Church operated from the 1870s until 1959 when the congregation joined with the congregation of the Lady Glenorchy Church in Roxburgh place. In 1960, there were discussions about whether to sell it and by 1963, the Victorian section of the church was demolished to make way for modern buildings.

The remaining Trinity Apse was preserved and can still be seen on Chalmers Close, though it is no longer open to the public.

Clare Stubbs

Imaging Supervisor

This post was edited to clarify the circumstances of the church’s construction on 7 January 2025.

Very well researched and interesting article. However, there is no evidence to say that King James II conceived the idea of founding Trinity College Church other than statements in the 19th century by writers of that time. The papal bull of 1462 in the Vatican archives state quite clearly it was Queen Mary who was the foundress. There is no contemporary evidence that James II himself conceived or initiated the project. The quote from the papal bull is

“Sane pro parte dilecte in Christo filie nostre Marie Regine Scotorum illustris nobis nuper exhibita petitio continebat quod olim ipsa de propria salute recogitans et ad caritatis opera maxime circa egenos et pauperes manus juxta evangelica documenta extendens dum adhuc clare memorie Jacobus II. Rex Scotorum vir ejus ageret in humanis quoddam Hospitale pro susceptione pauperum et egenorum eorundem extra oppidum regium de Edinburgh Sancti Andree diocesis construi et edificari fecit illudque dotavit et successive boni operis fructum provida consideratione attendens”

and my English extract is “while James II of clear memory, King of Scots, her husband, was still acting among humans she caused to be constructed and built a certain Hospital for the reception of the same poor and needy outside the royal town of Edinburgh, of the diocese of St Andrews,”

Grateful if you could clarify your text as other people have quoted your article.

LikeLike

Hi there: Thank you for your input on this post, as we’re keen to ensure it’s accurate. I’ve discussed this with the post’s author and, after investigating, we’ve amended the text to reflect your comments.

LikeLike