Warning

This contains materials and references to homophobic language and themes which may be upsetting for some individuals. Please take this into account before reading.

21 June 2025, marks the 25th anniversary of the repeal of the law known as Section 28 (otherwise known as Clause 28 or Section 2A). In this article, the bill will be referred to by its common name of Section 28.

To mark the anniversary, we explore our archives to uncover what Section 28 was, what people thought about it, the campaign to repeal it and to reveal the hidden LGBTQ+ history in Scotland and across the United Kingdom.

What was Section 28?

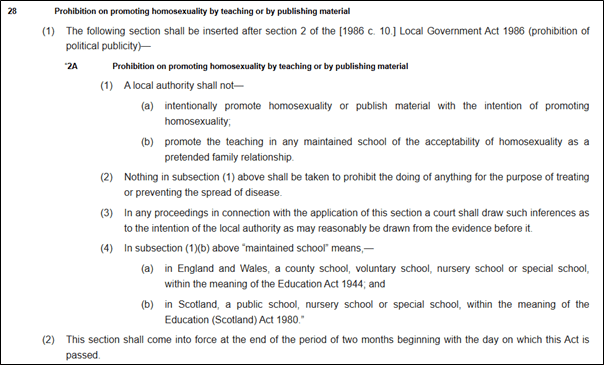

Section 28 was introduced by the Conservative Government led by Margaret Thatcher as part of the Local Government Act 1988.

The law banned the “promotion of homosexuality by teaching or publishing materials” and the teaching “of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.

Section 28 was considered a step backwards for the gay rights movement in Britain. It was enacted as a response to the negative public, social and political discourse around homosexuality which was exacerbated by the AIDS pandemic, a defining event of the 1980s.

The demonisation around the AIDS pandemic, as a so-called “gay plague”, created an environment of fear, anxiety and hatred toward LGBTQ+ people that was reflected in the British Social Attitudes surveys. In 1983 50% of those surveyed agreed that “sexual relations between two adults of the same sex” were “always wrong”. By 1987, the figure had risen to 64% [source].

The ambiguous wording of Section 28 meant that books and other content that included homosexuality were essentially ‘banned’, and, in schools, teachers were hesitant to discuss homosexuality whatsoever. This led to a lack of awareness of LGBTQ+ identities, homophobic bullying within schools and a lack of support from teachers who were wary of breaching the clause [source].

In our records

For this research, records from petitions submitted to the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee (SCP2/1/5) were consulted. This collection contains records from both the ‘Keep the Clause’ and ‘Protect our Children’ campaigns – key groups which opposed the repeal of Section 28 in Scotland.

Papers of the Scottish Parent Councils Association (SPCA) (formerly the Scottish School Boards Association) (SSBA) (GD529) are also held by NRS. School Boards were designed with the intent of increasing parental influence on the overall objectives and policies of the school; they were also to act as a body that could liaise between the school, parents and the wider community. As Section 28 effected school students, the stance of the SSBA was an important representative of parent and teacher views.

External records from the British Newspaper Archive, OurStory Scotland Archives, the Glasgow Women’s Library and the Equality Network were also consulted, to understand the effects, protest and campaigning around this law.

Section 28 in practice

Existing records give an insight into what it was like living under the effects of Section 28 in Scotland. There appears to have been significant confusion around the interpretation of its terminology. The use of the wording ‘promotion’ and particularly ‘intentionally promoting’ homosexuality was difficult to define from a legal perspective, and therefore difficult to interpret and implement for local authorities.

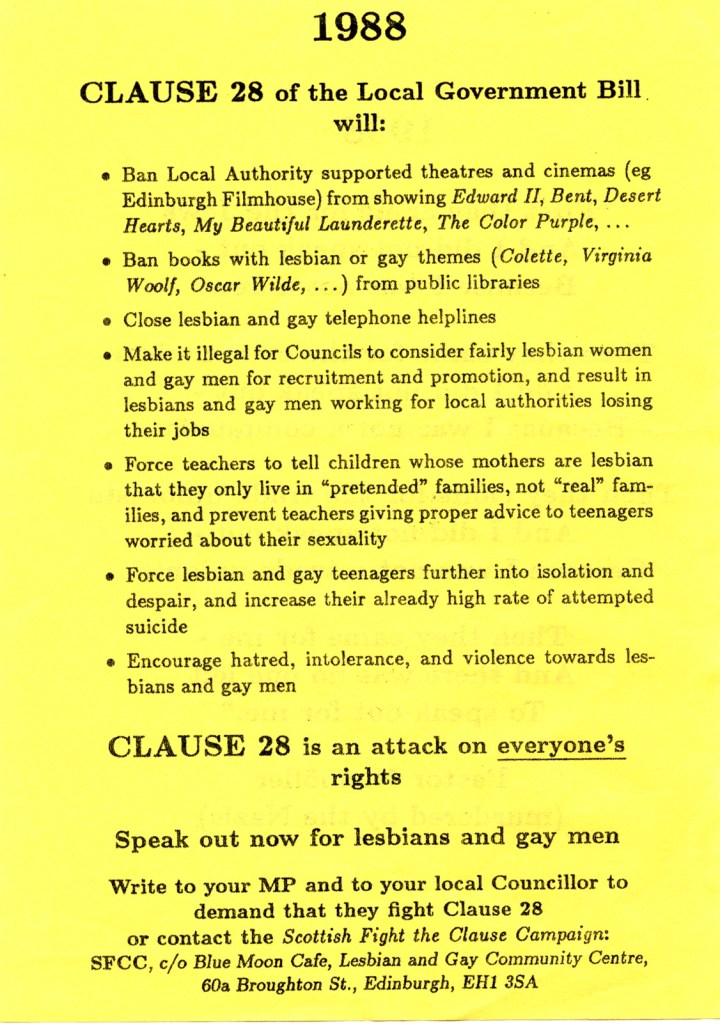

This poster identifies the risk posed to LGBTQ+ people across the United Kingdom due to the introduction of Section 28. Including closing LGBTQ+ support networks (funded support helplines and support in schools for students), reducing visibility, increasing isolation and perpetuating predjudice against LGBTQ+ people.

A list provided by the ‘Fight the Clause’ campaign detailed what the clause would potentially effect and what it would mean for LGBTQ+ people. This included school teaching, films, and theatre. Threats to job security and reinforcing prejudice toward LGBTQ+ people could be seen as indirect effects.

Effects of Section 28

“Unused but Dangerous” published by the Guardian further explains the large scope and uncertainty around the clause. This led to it being interpreted in different ways across the UK. Concerns around the arts, museums and LGBTQ+ charity funding are apparent through media coverage held in our archives.

In the 16 months since section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 took effect, not a single case has come to court. Not one outraged ratepayer or councillor has chosen to tax a local authority with “intentionally promoting homosexuality”…

“It’s an obscure and badly-drafted piece of legislation” says Madeleine Colvin, NCCL’s legal officer, “and we never expected a flood of test cases. It’s the self-censorship, the decisions taken by councils behind closed doors, that make section 28 so dangerous”

‘Unused but dangerous’, The Guardian, 11 October 1989

The article reveals that in Edinburgh, a Labour-controlled district council refused a grant for a half day music and poetry festival held by the Scottish Homosexual Action Group (SHAG) citing Section 28. This is despite the Labour Party opposing Section 28.

Another article, “Lesbian plea sparks anger”, published in the Edinburgh Evening News on 30 January 1991 highlights concerns around a similar grant request, and whether it would be ruled illegal under Section 28 . Beth Brereton, a Conservative councillor, opposed the grant for a Scottish Lesbian Gathering – questioning why the community would have to “pick up the bills” for those who “indulge in unnatural sexual acts”.

This caused backlash from women’s right activists accusing Brereton of perpetuating homophobic language and promoting prejudice.

The clause had little impact legally, however, socially, it has had a strong and lasting effect on the LGBT+ community. This may have been the main aim of the clause. As Conservative MP David Wilshire stated, some success in Section 28 was a “warning to liberal[s]… that you can go too far for a society to tolerate” as “the strident boasting arrogance of the homosexual community seems to have quieted down quite a bit” (‘Unused but dangerous’, The Guardian, 11 October 1989, page 27).

Ultimately, no individual was convicted under Section 28. However, it restricted the visibility of LGBTQ+ teaching, events, art and theatre.

Effects in schools

As discussion of homosexuality had the potential to be seen as an infringement of the law, many teachers were hesitant to speak about it, effectively reducing LGBTQ+ visibility for all children. Homophobic bullying and anti-gay prejudices were apparent in the schooling system, with nowhere for those being bullied to turn for help. This could be considered a reflection on the wider stance of the UK’s society.

For example, a study in Edinburgh reported that over a third of people interviewed had been bullied in school or college. Another study in Glasgow showed similar figures with a third of interviewees believing that their education was negatively affected by homophobia, with over half experiencing overt forms of homophobia [source].

“I’m grateful to Mrs Thatcher I don’t have to talk about perverts” was a reaction from students around sexual education in school (seen in image above).

The four-piece original artwork exhibit by Ian Passmore reveals the attitudes and perceived concerns about homosexuality. This prejudice was reflected across society around the time of the Section’s introduction, specifically affecting young LGBTQ+ students.

Censorship in art

Another perceived effect of the introduction of Section 28 was censorship. This was particularly evident in media, the arts and museums as newspaper clippings from the late 1980s demonstrate.

The National Campaign for the Arts were vocal in their concerns about the loss of expression and art “not just to homosexual artists, but to the artistic lives of us all would be lost” because of Section 28.

Notably, (Sir) Ian McKellen, actor and LGBTQ+ activist. McKellen came out as gay in 1988, despite concerns of negative effects on his career. He openly opposed the introduction of Section 28 and was a visible figure of protest against the clause.

Records reveal other top names from the British stage who rallied in opposition as it threatened the future of council sponsored drama. Performers, including Ned Sherrin, Simon Callow and Caryl Churchill, were among those present at Playhouse Theatre, London, to stand against the introduction of Section 28 and went to protest at the House of Lords.

Censorship of the local arts scene exemplified the indirect effects of Section 28 and how the legislation reached beyond LGBTQ+ lives and encroached upon UK arts and culture.

Our next post will explore those that opposed the Section and its eventual repeal.

Ben Scott

Customer Service Officer