- Topics, Words and Language featured

- Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department

- Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland

- Prisoner-patient: Marjory McKercher or McGregor

- Diagnosis

- A Guardian

- Resources used/further reading

- Mental Health Support

Records from the Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD) Case Books (HH21/48), covering admissions from 1846 -1902 have been added to Scotland’s People . These Case Books afford the opportunity to explore the lives of prisoners with mental health issues in the late 19th, early 20th century, and how they were treated.

Topics, Words and Language featured

This article features information and images from the Perth Prison CLD Case Books. These records, from the Victorian era, relate to the admission, treatment and release of prisoners with mental health issues in the 19th century. Terms and language from this historical context are present. As such there are several references to historical medical terms that are no longer medically accurate or acceptable. These include: lunatic, mad, imbecile, and insane. There are also descriptions of violence.

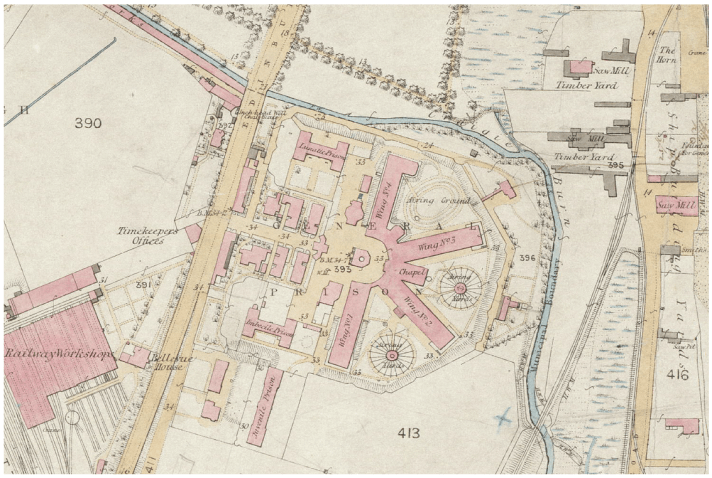

Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department

Prisons have a much higher proportion of men and women with mental health problems than the general population. This was also true in Victorian times, when ‘the liability of the criminal classes to an excess of insanity is very great, and much beyond that of the free population of the country ’(‘Criminal Lunacy in Scotland for Quarter of a Century, from 1846 to 1870’ by James Bruce Thomson, Resident Surgeon, General Prison for Scotland, at Perth). The Prisons (Scotland) Act (1844) defined ‘criminal lunatics’ as ‘insane persons charged with serious offences’. From 1846 Perth Prison provided specialist housing for those not responsible on account of their insanity and in 1865 established a separate Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD). The then-resident surgeon James Bruce Thomson called inmates ‘prisoner-patients’ or ‘state lunatics’, ‘inasmuch as, having committed grave and heinous crimes dangerous to the public, they are placed at Her Majesty’s disposal, under the care of the State.’ Criminal lunatics became part of an integrated system during Victorian times, rather than anomalies in both justice and health care.

Predating Broadmoor, England (1863) and Dundrum, Ireland (1850), Perth was the only such facility in Scotland until The State Institution for Mental Defectives (now The State Hospital) opened at Carstairs, Lanarkshire in 1948.

During the 1860s Perth Prison had about 600 inmates and 60 staff, with accommodation for 35 males and 13 females in the CLD. In 1881 a separate female lunatics’ wing opened, increasing capacity . Originally run by a board of management, Perth came under the Prison Commission for Scotland from 1877.

Offenders were admitted to the CLD not for the crime committed, but for the threat presented by their insanity. It contained, managed, and tried to make better, men and women with debilitating and dangerous mental health problems, prior to either transferring them to an asylum or prison or (from 1871) discharging them conditionally or unconditionally, after assessment of the risks posed to the community.

How do we know what the prisoner-patients had done and why? Crown lawyers conducted investigations called ‘precognitions’ prior to trial, amassing evidence from anyone who knew of the offence and the accused. Newspapers often mediated trial proceedings to the general public. Medically and legally qualified civil servants supervised admission, incarceration, and release. Physicians and surgeons collected histories before admission and kept detailed case notes as they tried to help sometimes dangerous, often vulnerable, but almost always complex and severely ill patients.

Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland

In 2019 NRS helped to develop and host the exhibition ‘Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland’. A partnership exhibition between NRS and guest curator Professor Rab Houston, University of St Andrews, a display of records was put on show in General Register House, Edinburgh. This exhibition was later developed into an online resource. This resource has recently been updated and provides:

- Examples and information on the records used to trace the history of prisoners with mental health issues

- A selection of prisoner-patient profiles exploring their life and treatment

- A printable, free-to-download version of the original exhibition for public use

This can be viewed on the NRS website here.

By examining the rich and varied history of the prisoner-patients, the exhibition’s aim is to raise awareness of mental ill-health inside and outside prisons because, regardless of circumstances, anyone’s life can be tragically affected by them. Highlighting the treatment of prisoner-patients in a society with very different medical science, laws, welfare systems, conceptions of the rights of individuals and communities to those today allows us to reflect on the same issues now, and approach those suffering from mental ill-health with better understanding and greater compassion.

Prisoner-Patient: Marjory McKercher or McGregor

Admitted to the Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD) on 24 May 1861. Marjory McKercher or McGregor* murdered George Munro, her illegitimate son, aged four.

Child murders made up half the female admissions to Perth’s CLD, these mostly of older, rather than new-born infants.

Diagnosis

There were two strands to how contemporaries understood Marjory’s horrific act. The first was ‘derangement of religious thoughts’, Marjory being an avid attender of the radical Free Church of Scotland that flourished in her native Highland Perthshire. Victorians believed misdirected religious devotion could manifest and cause derangement, especially among women, whose minds, they thought, were weaker than men’s.

“Afraid of the devil…her mind tossed between hope and despair, sleepless, attempted to throw herself out of the window, thought herself lost, dying, burning secretly and suddenly got hold of a razor and cut her child’s throat and then attempted her own. The opinion of the witnesses was that revival excitement had brought on this paroxysm of insanity. A few Sundays before she spoke out in prayer in church and the clergyman thought her mind was wrong (afflicted), very ignorant of the Scriptures, mind considered by several witnesses not strong; got drunk at times. When calm she looked sane, but now and then became suddenly mad on her way to Perth and outrageous.”

HH21/48/1 p95

Both legal and medical authorities looked closely at personal morality because they thought insanity was the result of failures in character.

“She is reported to have been a very loose character, at one time on the poor roll. She has had two illegitimate children and has lived with other men, previous to her marriage with her present husband, who is said to be a weak fellow.“

HH21/48/1 p93

Petite at 4 feet 10 inches tall (1.5m), with a fresh complexion, black hair, and grey eyes, Marjory spoke, when first imprisoned, of ‘the wickedness of her past life’. She said, the devil came to her and told her that reading the Bible would stop her getting to ‘the good place’. Asked about the murder, she said she ‘believed that she and her boy were “in the bad place” and that to get out of it, her duty was to cut her own and the child’s throat’. But a few days later she spoke of ‘the love she bore him and with sorrow and remorse at the deed she had done, recalling with convulsive weeping the parting smile of her child as she was to seize the murderous weapon’.

A guardian

Marjory’s homicidal attack was a one-off and she made good progress in her early years at Perth, first conditionally released in 1875. Prisoners under conditional release were required to secure a guardian; a stipulation which some found difficult to fulfil. Private individuals responsible for their supervision, Guardians were legally answerable to the Scottish Office. The records note that ‘her friends [relatives, including two married sisters living in Perthshire] are not at all likely to come forward’ and the compassionate householders who did take her in sooner or later thought better of the arrangement.

From the CLD Case Books we know that Marjory was a widow and that she remarried in 1877. Alexander Thomson was another prisoner-patient in Perth. He was admitted to the prison on 13 May 1865 for murdering his wife, Margaret Thomson (nee Dickson). In the autumn of 1877 Marjory and Alexander married; both had been conditionally liberated from the CLD. In Alexander’s Case Book his marriage is recorded in the notes for 31 October 1877:

“Been conditionally liberated for some years. Is conducting himself well [and] working busily. Married (much to my dissatisfaction) another conditionally liberated lunatic Marjory McKercher or McGregor”

HH21/48/1 p175

Alexander’s condition was identified as ‘alcoholic mania’. His liberation included an agreement from that he would refrain from drinking. Alexander broke this condition and was re-admitted in September 1878. Marjory was re-admitted shortly afterwards in December of the same year. A few years later Alexander died in 1888 and Marjory was once again widowed.

By the 1880s resident and visiting medical men were unanimous that ‘hers is really a deserving case’ for discharge. Between 1877 and her unconditional discharge on 11 February 1907, at the age of 74, Marjory went through several guardians and two readmissions.

We last read of her living with a married niece in Dundee, working as a cleaner.

To explore the recent addition of Perth Prison records to Scotland’s People, read the ‘Prison registers’ record guide.

Resources used/further reading

- NRS, Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department Case Book access via Scotland’s People, HH21/48

- Prison Registers Guide

- *In the Prison Registers, all ‘Mc’ surnames have been expanded to ‘Mac’ to account for inconsistencies in the rendering of Mc, Mac and M’ names by the recording clerk.

- NRS, Criminal Lunatic’s files, Mckerchar or McGregor or Thomson, Marjory. HH18/51

- NRS, Criminal Lunatics (Perth) records, Thomson or McKercher or McGregor, Marjory. HH17/107

- Criminal Lunacy in Scotland for Quarter of a Century, viz., from 1846 to 1870, both inclusive. By J. Bruce Thomson, L.R.C.S. Edinburgh; Resident Surgeon, General Prison for Scotland at Perth .

- Promoting mental health through the lessons of history, Professor Rab Houston, University of St Andrews

Mental Health Support

If you, or somebody you know, would like mental health advice or support you can contact the following resources:

- Samaritans

https://www.samaritans.org/scotland/samaritans-in-scotland/

Call 116 123 for free, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year

Email jo@samaritans.org if you would prefer to discuss any issues electronically - The Scottish Association for Mental Health

https://www.samh.org.uk/ - Mental Health Foundation Scotland

https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/scotland - Breathing Space Scotland

https://breathingspace.scot/

0800 83 85 87 - NHS Suicide Information, Support and Resources

https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/mental-health/suicide - NHS Moodzone – Resources for Stress, Anxiety and Depression

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/ - Penumbra

http://www.penumbra.org.uk/services/

One thought on “The Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic Department”