Following our post ‘Part 2 – Tytler and the Grand Edinburgh Fire Balloon’ from last week, we continue the story of James Tytler.

Image credit: www.archive.org. Public domain

The success Tytler found in launching and piloting his fire balloon in August 1784, was sadly not to last. The following year, 1785, in March we find him in the records, registered once more in Holyrood Park Debtors sanctuary. He is described as a ‘chemist and baloonmaker’.

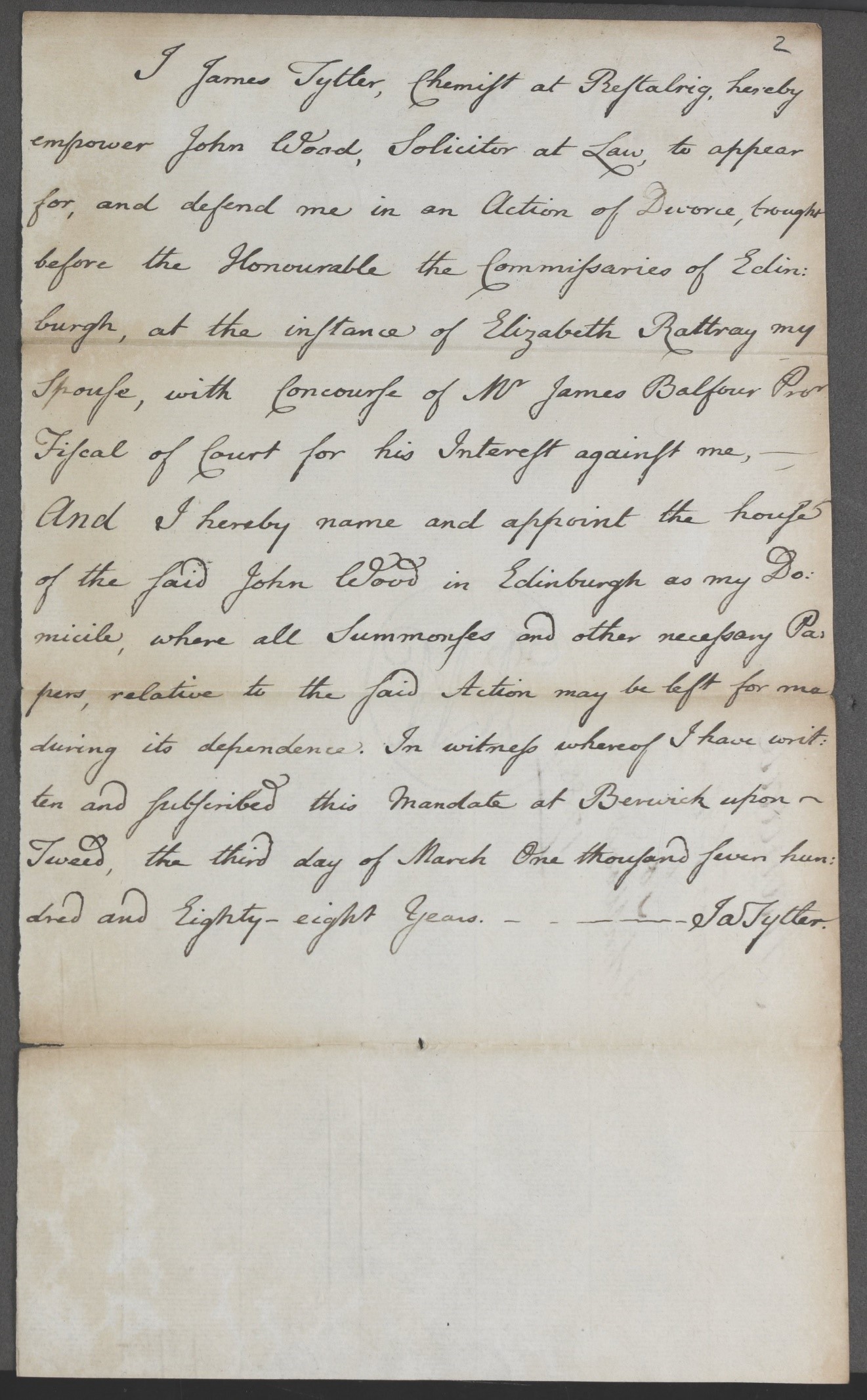

Further strife would follow when Elizabeth Rattray petitioned for divorce in 1788. The court citation noted that Tytler ‘totally withdrew his affection from the said complainer his spouse and obliged her to leave his house’ and shortly afterwards ‘took up with another woman of the name Cairns.’ It is unclear who Cairns was, but the other paramour mentioned in the court papers is known. Jean Aikenhead ‘who he also calls his wife and is now living and cohabitating with her as such and has had twin children by her.’ (NRS, CC8/6/803).

(Crown copyright, NRS, CC8/6/803 page 12)

It seems at least that Tytler intended to marry Jean, as their proclamation of banns were announced at St Cuthberts parish on 7 December 1772, but no trace of their marriage has yet been found.

After his financial troubles and divorce proceedings, little is known about Tytler’s activities until 1791. In this year, Tytler returned to Edinburgh and started work on a number of scholarly publications which included the Historical Review which appears monthly between July 1791 and July 1792. In the Historical Review Tytler commented favourably upon the French Revolution and discussed Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) which proposed, now commonplace, welfare provision such as old age, pensions, and maternity support. Tytler became a member of the Scottish branch of the radical ‘Society of the Friends of the People’, which advocated parliamentary reform. It was in this context that Tytler wrote and published his pamphlet ‘The People and their Friends’ which called for the King to be petitioned to reform parliament and went as far as calling the House of Commons a ‘vile juncto of aristocrates’.

In the aftermath of publication Tytler fled Edinburgh, having been ‘ten times called in Court and three times at the door of the Court House he failed to appear’. On 7 January 1793, the Judge declared Tytler to be ‘an Outlaw and fugitive from his Majesty’s Laws and Ordain him to be put to His Highnesses horn and all his Moveable goods and gear to be escheat and in brought to his Majesty’s use for his Contempt and disobedience in not appearing this day.’ (NRS High Court Minute book, JC7/47/67). Tytler was by now in Ireland with Jean and their twin daughters until they could fund a passage to America. In America he hoped to find the freedom he had often read and written about. Tytler and his family settled in Salem, Massachusetts where he edited the Salem Register and published his last great work ‘A Treatise on the Plague and Yellow Fever’ in 1799. James Tytler died in 1804 after his body was found in the waters of the nearby Neck Gate’s north shore. Jean, his widow, made a meagre living by making up Tytler’s medical preparations to sell but died in a Massachusetts alms house in 1834.

Tytler remembered

Despite his achievements as editor and balloonist, today James Tytler is not a well-known name. Tytler’s contemporary Robert Burns gave an insightful and memorable description of ‘Balloon Tytler’, having probably met him during a visit to Edinburgh. Tytler had turned his hand to writing lyrics to traditional tunes and is published alongside the bard in Scots Musical Museum (1787). Tytler is said to have written ‘The Bonnie Brucket Lassie,’ amongst other ballads, on which Burns comments, but also upon its surprising composer:

“The two first lines of this song are all of it that is old. The rest of the song, as well as those songs in the Museum marked T, are the works of an obscure, tippling, but extraordinary body of the name of Tytler, commonly known by the name of Balloon Tytler, from his having projected a balloon: A mortal, who though drudges about in Edinburgh as a common printer, with leaky shoes, a sky-lighted hat, and knee-buckles… that same unknown drunken mortal is author and compiler of three-fourths of Elliot’s pompous Encyclopaedia Britannica, which he composed at half a guinea a week”

(Reliques of Robert Burns, 1759-1796 (1806))

Tytler is remembered for his work on the Encyclopaedia Britannica and his attempts to create and fly his balloon in the skies above Scotland’s capital. He lived a life of poverty and invention ; his failed enterprises only spurred him on to try another. Happily, his name lives on within the streets of Edinburgh. Tytler Court and Tytler Gardens built on the site of Comely Gardens where his balloon successfully soared were named in his honour, Britain’s first aeronaut.

Jessica Evershed

Outreach and Learning Archivist