When the foundation stone of the new Register Office or Register House was laid on 27 June 1774, it was the culmination of a long struggle to create a home for Scotland’s national records. For decades, efforts had been made to make proper provision for the historic public records, which Article 24 of the Act of Union had stated were to remain in Scotland permanently. Until they were moved into the newly-built Register House from 1788 onwards, they had languished in poor storage conditions either in the Laigh Parliament Hall or in the offices or dwellings of the keepers and creators of the various public registers that were scattered around the High Street and Lawnmarket, to be near the Court of Session.

The senior crown official responsible for the creation and upkeep of many of the public records was the Lord Clerk Register, and during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries successive holders of the office tried, and largely failed, to improve storage conditions. Some responsibility for the creation of suitable accommodation for the records and the clerks rested with Edinburgh town council, but the opportunity was lost to include space within the new Exchange building completed around 1760. The small remaining fund was put towards the projected new bridge across the valley of the Nor’ Loch. In April 1766, soon after work on the ‘North Bridge’ began, the town council launched a competition for a plan of the ‘new town’ which was famously won by James Craig. An amended version of his plan was approved in August 1766, and feuing of plots in the New Town began.

Meanwhile, in 1760 a new and dynamic Clerk Register was appointed. James, 14th Earl of Morton, was a dedicated public servant and man of science, who tackled his new responsibility with unprecedented vigour and rigour.

After carrying out an inspection of the record accommodation, in 1762 a ‘memorial’ or memorandum went to government, making a convincing case for creating a proper repository for records which it was argued were at risk. It suggested that income from the estates of Jacobites who had been forfeited after the ‘Forty Five rising could be used to pay for the proposed building. In 1765 the Crown duly granted £12,000 from these funds, and commissioned several leading public officials and judges in Scotland to serve as Register House Trustees.

Morton had already begun his search for a suitable site in what was soon to be Edinburgh’s Old Town. Several places were investigated in turn during 1763-1765: ground behind the Excise Office in the Cowgate, ruinious burgh buildings behind Parliament Close, and a corner of the garden of George Heriot’s Hospital. Nearness to the Courts was a key factor, but Morton was also determined to avoid the risks of fire inherent in a building of several storeys.

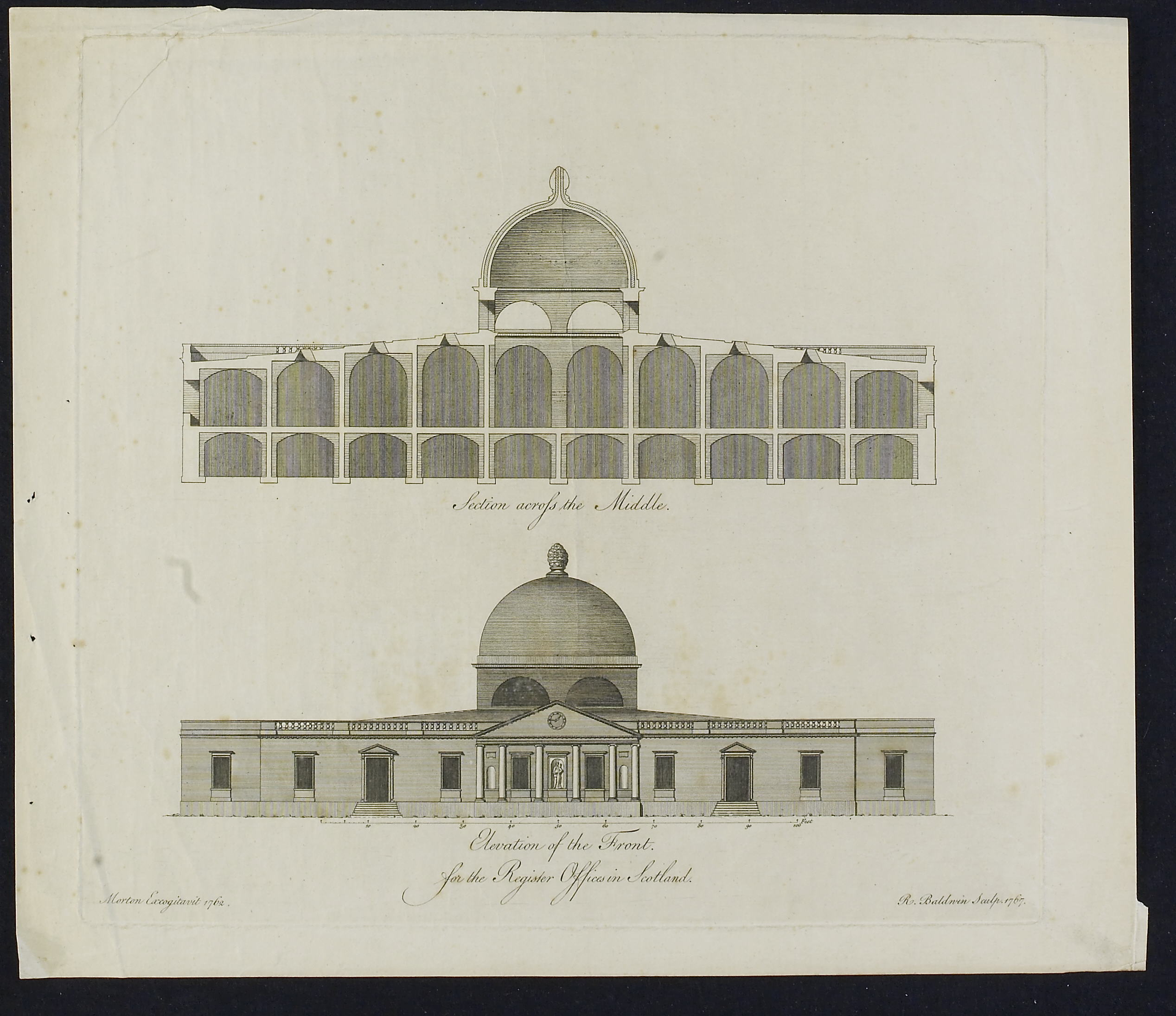

In 1762 his thoughts took the form of drawings, which he had engraved in 1767. He envisaged a square building with four ranges of offices, about half of which were for the Court of Session clerks, while the rest were allocated to the other public offices such as the Sasine Office and the Teinds Office. At the centre was record storage, with a search space at the centre lit by windows set in the drum of a dome. Although Morton’s design was schematic and could not have actually been built from his plans, Robert Adam’s more sophisticated building essentially followed Morton’s arrangement with a quadrangle of office ranges enclosing a central record storage space with a dome at its heart.

Owing to a long gap in their minutes from 1766 until 1768, we do not know when the Trustees began to consider a site in the New Town. In early 1767 Morton had tried and failed to force from the town council the grant of a site on the ridge of the New Town and other concessions. Probably later that year two sites were being considered for a building of exactly the size of Morton’s design. This plan shows the site at Multrieshill that was eventually chosen, which then consisted of a patchwork of privately-owned ground, edged with land owned by the town. West of the northern end of the North Bridge stood the second potential site, with the advantage that it was entirely owned by the town. It was later developed as houses and shops, and is now the site of the Balmoral Hotel.

After Lord Morton’s death in October 1768, Lord Frederick Campbell succeeded him as Lord Clerk Register. In August 1769 part of the North Bridge collapsed, just as it was nearing completion. The town council was anxious to complete this crucial infrastructure, and after a series of negotiations with the Trustees, gave them their ground on the coveted site facing up the North Bridge. For their part, the Trustees gave up any further claim against the council regarding a register house.

Agreement was reached on 21 September 1769, when this plan was signed on the back by James Montgomery, the Lord Advocate, and James Stuart, the Lord Provost. Almost three years passed before the contract was signed which set in motion the construction of Register House to Robert Adam’s design. Even before its elegant facade was finished the historian of Edinburgh, Hugo Arnot, was describing it as ‘perhaps the handsomest building in the nation’. When it was eventually completed in the 1820s, Register House fulfilled the Earl of Morton’s enlightened and practical vision by providing a proper and long-lasting home for Scotland’s public records.

Dr Tristram Clarke