In August 2023 Scotland successfully hosted the UCI Cycling World Championships. This was the biggest cycling event in the world. Spanning two weeks in venues across the country, the Scottish public was treated to a festival of cycling, featuring the world’s best cyclists, including Scots such as Katie Archibald, Anna Shackley, Fin Graham and Charlie Aldridge competing in road, track, BMX and mountain bike events. Inspired by the passion of the competing athletes, we decided to explore the collections of National Records of Scotland (NRS), to trace the history of the bicycle and how it has transformed peoples’ lives.

Scotland played an instrumental part in the development of the bicycle; a Dumfriesshire blacksmith McMillan Fitzpatrick (1812-1878), has a claim to have invented the first pedal-driven bicycle in 1839. McMillan’s invention was driven by a system of treadles attached to the rear wheel. McMillan had built his machine solely for his own use, primarily to undertake the 70 mile journey to his sister’s home.

The commercial potential of the machine was soon evident, but as McMillan had not patented the design, other manufacturers in Scotland were free to produce and sell versions of McMillan’s machine. Gavin Dalzell of Lesmahagow, produced a version in 1845-46 which is believed to be the oldest rear wheel driven bicycle in existence.

The design of the bicycle advanced in the second half of the nineteenth century. In France, the bicycle evolved into the ‘velocipede’, and unlike McMillan’s earlier design, was equipped with pedals attached to the axle of the front wheel. The front wheel was generally larger than the rear, in order that each pedal revolution would propel the rider further. This arrangement was soon taken to extremes in the quest for ever greater speed, and by the 1880s the velocipede was developed into one of the most iconic bicycle designs, ‘The Ordinary’ or ‘Penny Farthing’. While the Ordinary was fast, by the standards of the nineteenth century, it was not particularly safe or comfortable and the risk of ‘taking a header’ over the handlebars was ever present; its wooden wheels and iron-clad tyres did little to soak up rough and often unmade roads. As such, the bicycle remained largely the preserve of hardy and wealthy sporting enthusiasts.

Within a few years, two developments would transform the bicycle from a plaything of the rich, into a practical form of transport. The first of which was the development of the Rover ‘safety bicycle’ by John Kemp Starley in 1885. Instantly recognisable as the ancestor of the modern bicycle, it employed a diamond shaped frame, wheels of equal size and allowed the rider to touch the floor while mounting and dismounting. Like McMillan’s treadle-powered machine, the new safety bicycle was rear wheel-driven by using a chain attached to two sprockets, multiplying the effort from the pedals. When this was combined with the development of pneumatic tyres by another enterprising Scot in the form of John Boyd Dunlop, the bicycle became a more attractive proposition for a wider audience, especially women. While infinitely more practical than its predecessor, a safety bicycle remained an expensive purchase and it was young women of the upper classes who were early adopters of these new machines, including those who attended university.

The young ladies of the upper classes were the first to embrace the dropped frame safety bicycle, seen here in ‘R Varty’s’ advertisement of 1897.

National Records of Scotland, Court of Session records, CS96/6980

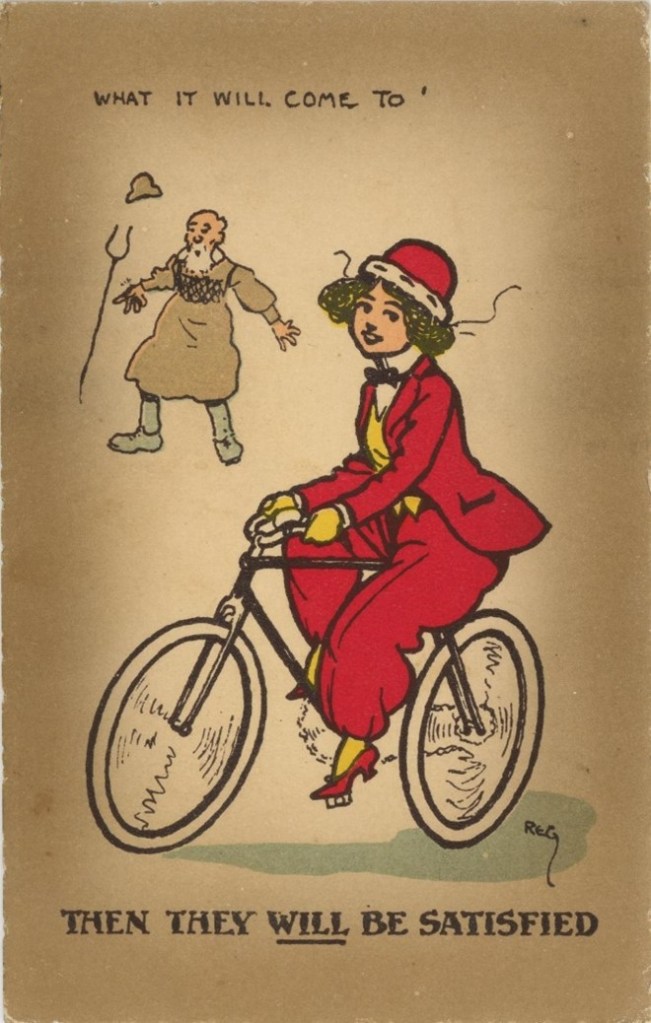

Women and cycling

Cycling was one of the few activities in which young unmarried women could undertake without a chaperone. Groups of women cyclists or even lone female cyclists, could venture out into the countryside unescorted. The freedom that these two-wheeled contraptions gave to women of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries cannot be underestimated, allowing women of the upper-classes to undertake philanthropic work or move around university cities.

As the cost of mass-produced bicycles became more affordable for the working classes, employment out of local areas could also be pursued. In one example of the usefulness of the bicycle, Fassiefern C. Bain of Lochmaddy writes to the Congested Districts Board with a ‘peculiar application’ for them to fund a ‘bycle’ for the North Uist District Nurse. The bicycle would enable ‘the one’ nurse to ‘better overtake her work….. I think you will agree with me it is a most worthy object and I think those of your Board who know the Island will agree with me that it is impractical for any one to overtake the work without a Bycle. I hope you will lay this before your Board, if not for its merits at least for its uniqueness’. Seemingly the board did not share Bain’s belief in the transformative power of the bicycle and the application was turned down, as documented below:

National Records of Scotland, AF42/2587

The applicant, Fassiefern Cameron Bain, has been found enumerated in Scotland’s 1901 census in North Uist and listed as a ‘Contractor’s Wife’, aged 40 (Crown copyright, NRS, 1901 census, 118/3 8/ 2). Her distinctive name may indicate that she was related to the Camerons of Fassiefern, a distinguished military family of Inverness-shire.

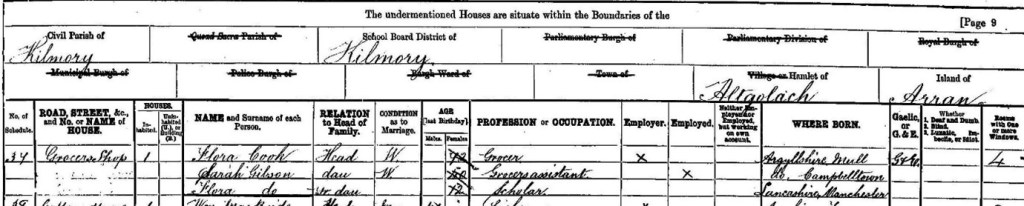

From the collections of Glasgow Women’s Library, with kind permission

The self-propelled bicycle was a symbol for the emancipation of women and it was soon taken up by the Suffragette movement. Flora Drummond oversaw the organisation of the Women’s Socialist and Political Union (WSPU) Cycling Scouts which were formed in 1907, and were tasked with spreading the women’s suffrage campaign beyond urban areas on bicycle. Their bicycles were often decorated in the flags of the WSPU and would cycle to villages outside large towns and “get on a chair or a box, as the case may be, form our cycles into a group around it, and deliver the gospel of votes to women” (Interview with Flora Drummond, Pall Mall Gazette). Drummond (maiden name Gibson), was born in Manchester, spent her formulative years in and around the Isle of Arran and Campbelltown where her mother originated.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, 1891 census, 556/3/9 page 15

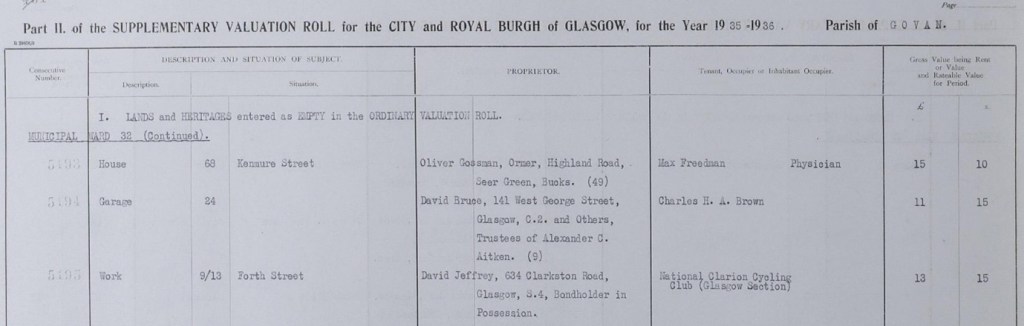

Drummond and her husband moved to her birthplace of Manchester and were early members of the Clarion Cycling Club, an organisation formed ‘for the purpose of Socialist propaganda and for promoting inter-club runs between clubs and different towns’. This application of the bicycle to spread a political message further afield no doubt inspired Drummond and the WSPU Cycling Scouts and the bicycle was a vital campaigning tool in the quest for equal votes.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Valuation Rolls for Glasgow Burgh, VR102/1572/142, page 142

While the original ‘bike boom’ of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century has passed into historical memory, the twenty-first century has seen its very own bike boom. Inspired in part by athletes such as Sir Chris Hoy’s six Olympic gold medals between 2000-2012, alongside a growing interest in making greener choices when travelling, bike use as a form of transport and recreation has grown exponentially. The Clarion club of which Flora Drummond was an early member, still has sections in West Lothian and Coatbridge. Newer organisations such as Pedal on Parliament still use pedal power to convey a political message, using organised group rides to advocate for better, safer and more inclusive cycling conditions in Scotland.

The bicycle came into its own in the COVID-19 pandemic. People across Scotland dusted off long forgotten bikes or purchased new ones and took advantage of exploring their local areas at a time when there was fewer cars on the road. The bicycle also served as a socially distanced form of exercise at a time when gyms and sports clubs were closed. Research by Cycling Scotland demonstrated that bicycle use in Scotland in 2020-2021 was up 47% on pre-pandemic levels, with the biggest increase coming from women and girls. The recent UCI World Championships will add to this legacy, inspiring diverse groups across Scotland to consider how an invention that has its origins in an blacksmith’s shop in Dumfriesshire, could change their world.

Jessica Evershed

Archivist

What inspired the decision to explore the history of the bicycle and its transformation in Scotland? Telkom University

LikeLike

How did Scotland contribute to the early development of bicycles, and what role did Dumfriesshire blacksmith McMillan Fitzpatrick play in this history?

Regard Telkom University

LikeLike